From Apathy to Action: How Youth Service-Learning Programs Can Inspire Ocean-Positive Action

An Ocean Bridge ambassador Op-Ed

Bryant M. Serre is a PhD student at Toronto Metropolitan University, in the Urban Water Centre. He is a 2023 Ocean Bridge alumni, whose current work involves assessing the impact of common de-icers (road salt) on sensitive primary consumers within the Toronto and Region Area of Concern. Bryant is also a member of the Steering committee for SETAC’s Freshwater Salinization Working Group, and continues to work collaborative with federal (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada) and local (Toronto and Region Conservation Authority) partners working towards determining the health of zooplankton in Toronto Harbour.

From Apathy to Action: How Youth Service-Learning Programs Can Inspire Ocean-Positive Action

Earlier this summer, I found myself standing at the mouth of the Saguenay River where it converges with the Saint Lawrence. On top of bedrock and granite shores, forged under tremendous pressure when glaciers receded north over 125,000 years ago. While I have learned about rivers, lakes, and wetlands most of my life, I am still gobsmacked whenever I see the vastness of the river as it opens towards the lower estuary and gulf. The place where water from our Great Lakes will soon make its way out to the Atlantic Ocean. Proverbially, ‘seeing is believing,’ as there is immense value in experiencing an environment firsthand, which evokes deep feelings of care.

Apathy among climate fighters

While the Earth’s environment has been a matter of urgent concern over the last several decades, it has not been so for the past 125,000 years. In aquatic environments — from the sediment at the bottom of lakes and rivers, up to the water’s surface, to the shores which one housed diverse wetlands, and thriving ecosystems, and all the organisms in between — change echoes throughout.

While many people are deeply aware of today’s environmental issues, action has notoriously lagged. To those who feel helpless, David Attenborough notes how “the greatest threat to our planet is apathy”. When we feel our individual action is not enough, fear paralyzes us, preventing us from doing what is needed.

I study Daphnia spp. (or water fleas) in my PhD at Toronto Metropolitan University and see the response to changes in our environment as one in the same. For the Daphnia, we know they are stressed by their environment when they fail to do the things they ought to do. Some take a downward spiral, some move erratically, and some get so worn down that they fall to the bottom of the tank: defeated.

To our Daphnia, we know it is not your fault: that is just how organisms respond to stress. To all of us, it is all the more reason we need to move past worry and seek a way forward. Looking back to what has worked in the past, particularly in the 1970s environmental revolution, there is great evidence to suggest that we can get there again.

History of North American Environmental Education

Starting originally as a teach-in, the first Earth Day on April 22nd, 1970, co-led by Republicans and Democrats, brought nearly 1 in 10 Americans to learn about the environment. It was through informing, engaging, and empowering children and adults that Canada and the United States saw decades of massive environmental restoration in both freshwater and marine environments. Significant national policies, like the Clean Water Act and the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement set the foundation for numerous laws improving terrestrial and aquatic environments. Likewise, the public supported the creation of thought-leading institutions, like the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Canadian Centre for Inland Waters (CCIW), which sought to work collaboratively with schools, families, and businesses to build a consensus that caring for our natural environment is paramount.

This legacy for education first, draws on the decades of environmentalists who first turned to instructing kids in and outside of schools, and even adults, on the importance of caring for our shared natural environment. Jack Vallentyne, a Great Lakes scientist who played a foundational role in shaping many of these environmental laws and institutions, embarked on a unique mission. He strapped a globe to his back, and stepped into classrooms, perilously worried that kids of the 80s-90s needed to care much more for the environment. More recently, a report authored by Learning for a Sustainable Future (LSF), an educational organisation at York University, Canada, interviewed both parents and students – the findings revealed that simply mentioning environmental issues in the news does not suffice to empower youth with the capacity or knowledge to drive meaningful environmental change. Discouraged, many become apathetic.

Environmental Education in the 21st Century

Growing up in Southern Ontario, I was fortunate to attend an environmentally-minded public school, which led me to pursue a bachelor’s in Environmental Studies and a master’s in Natural Resources. However, even with two decades of learning about the environment, more than most, I still left feeling that I did not know what to do — or how to make change. Rather, and overwhelmingly-so, we had only been taught what is wrong with the environment. In conversation with my peers, this is unfortunately too common.

In Ontario, the first-female Canadian astronaut, Roberta Bondar, and longtime proponent of environmental education, argued for its inclusion in all aspects of the educational curriculum in 2007. This would mean you could learn about the water cycle in your Grade 4 science class, and in your Grade 10 history class, learn about the implications of Settlers draining wetlands. However, since it was mandated in 2009 under Ontario’s “Acting Today, Shaping Tomorrow” framework, it is rarely brought into all classes. During my master’s program at McGill’s Agricultural and Environmental Science campus, where I instructed a laboratory section for a final-year geography course, I was surprised to observe comparable experiences among students. Students would often express how they would love to learn more about how they can act, rather than solely learning all that is wrong with the world. If we seek now to make change during this critical decade of climate action, an environmentally-minded population with the ability to act, is paramount.

Ocean Wise’s Roots in Public Education:

I was drawn to Ocean Wise early, learning about their history as early purveyors of building environmental knowledge among children and adults in Canada. Starting in 1951 as the Vancouver Aquarium, Ocean Wise brought in tremendous expertise — including naturalists, biologists, and wildlife specialists — to educate the public on the importance of protecting and restoring a diversity of freshwater and marine life throughout their enclosures.

For over seventy years, Ocean Wise has continued educating the public, focusing on cultivating an environmentally-minded population to reach their goals of combating climate change, overfishing and plastic pollution. Foundational to all these efforts, is education. Through Ocean Wise’s learning programs, they reach over half a million youth yearly, and many more through their youth service-learning programs. For urban youth, they bring the ocean to the classroom with an immersive “Sea Dome” experience, engaging community members in shoreline cleanups, and providing learning kits to teachers to help their classes learn about ocean plastic, the interconnectedness between humans and their environment, and understand what it means to be a species at risk.

In Ocean Wise’s youth programs, youth across Canada, between the ages of 15-30, can participate in various programs to build their foundational environmental knowledge, capacity, while being empowered to make changes in their own communities through service-learning projects and placements.

Participating in Ocean Bridge

This past summer, I was a participant in Ocean Wise’s Ocean Bridge program, which is a five-month program for Canadians and permanent residents ages 19-30, with cohorts across Canada. Within the Saint-Lawrence cohort, I found space to form deep connections with like-minded peers, cultivate community, and gain hands-on experience. This allowed me to learn firsthand, in both remote and urban settings, about protecting our vital water resources.

There are several accounts written by Ocean Bridge alumni that speak to the importance of being immersed in a community of like-minded peers. It is important nevertheless to reiterate how inspiring it felt to be surrounded by so many passionate folks who wanted to learn the foundational skills and knowledge of the environment, on which we could build upon to make change in our own communities. With backgrounds in film, graphic design, business, policy, through to those in science, it is rare to have a learning environment where all folks are learning together and collaborating towards solving issues. It harkens back to what these maverick institutions were all about: where all interested parties are at the table together, working towards a solution; leading empathetically and collectively, and not alone.

Exploring the St. Lawrence basin is a rare privilege, where the breathtaking view of the Prince Shoal Lighthouse becomes an educational backdrop. Here we delve into the intricacies of how deep, cold polar currents move upwards and mix with outgoing water from the Great Lakes and the Saguenay River. Or, along the rocky shoreline, where we explore the region’s biodiversity with divers who retrieve various crustaceans, starfish, and sea urchins from the river’s depths.

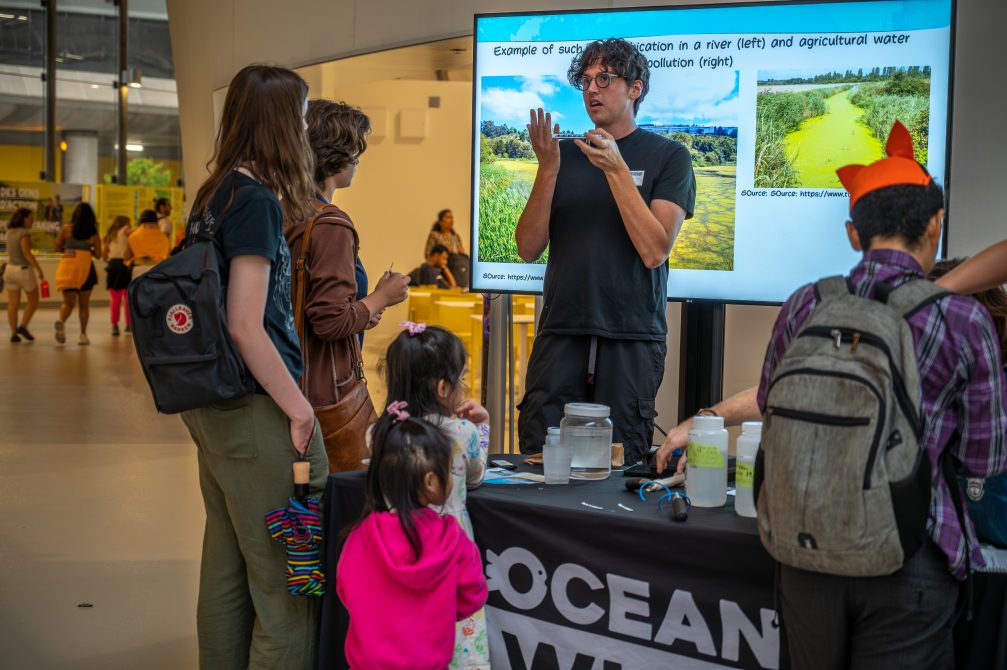

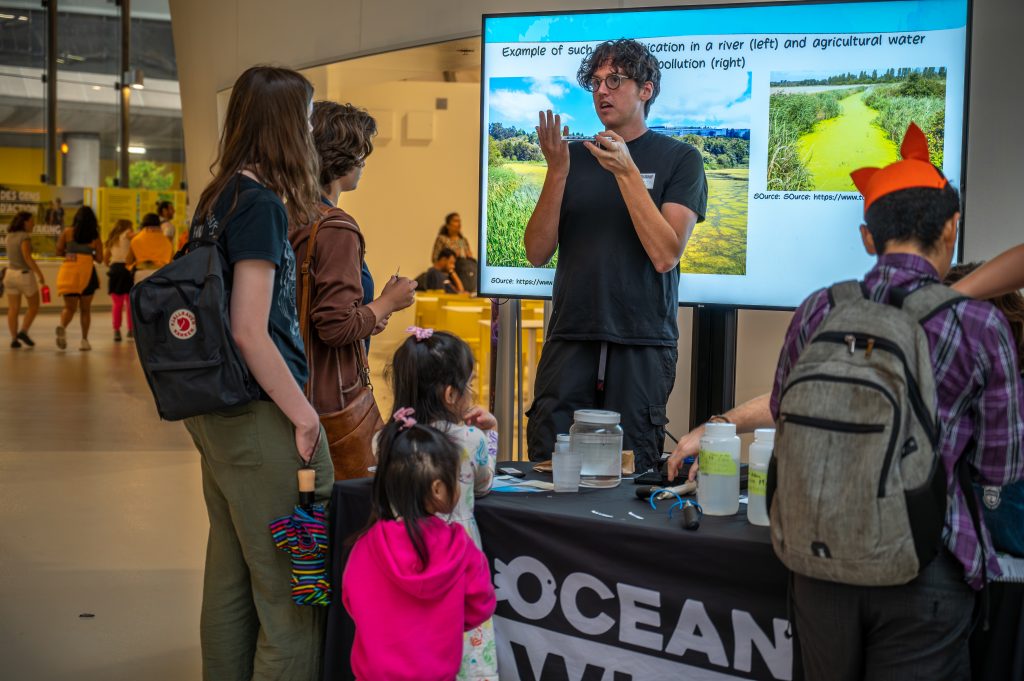

Later in the summer, our program reconvened for one more learning journey. Through Ocean Wise’s partnership with the Biodome, in Montreal, it felt as if we were channelling Ocean Wise’s origins at the Vancouver Aquarium. Our mission: educate children of all ages on the importance of clean lakes, rivers, and our oceans. At one of our informational tables, we taught kids about water quality, and why processes like algal blooms can be bad for fish, or why applying too much road salt affects our lakes and oceans.

Since starting my doctorate studies, I often reflect on my experience in the Ocean Bridge program. It is an everyday mission of my Ocean Bridge peers and I to not just let people know about the environment, but instil deep care, and foster love towards the environment, thus protecting it. This experience is something I carry with me every day: the importance of collective action on our environment. Indeed, it is so critical that people, together, get out and learn about the environment. Our planet needs us.

Posted March 14, 2024 by Alex Leroux