Big Attention for the Ocean in the Big Apple

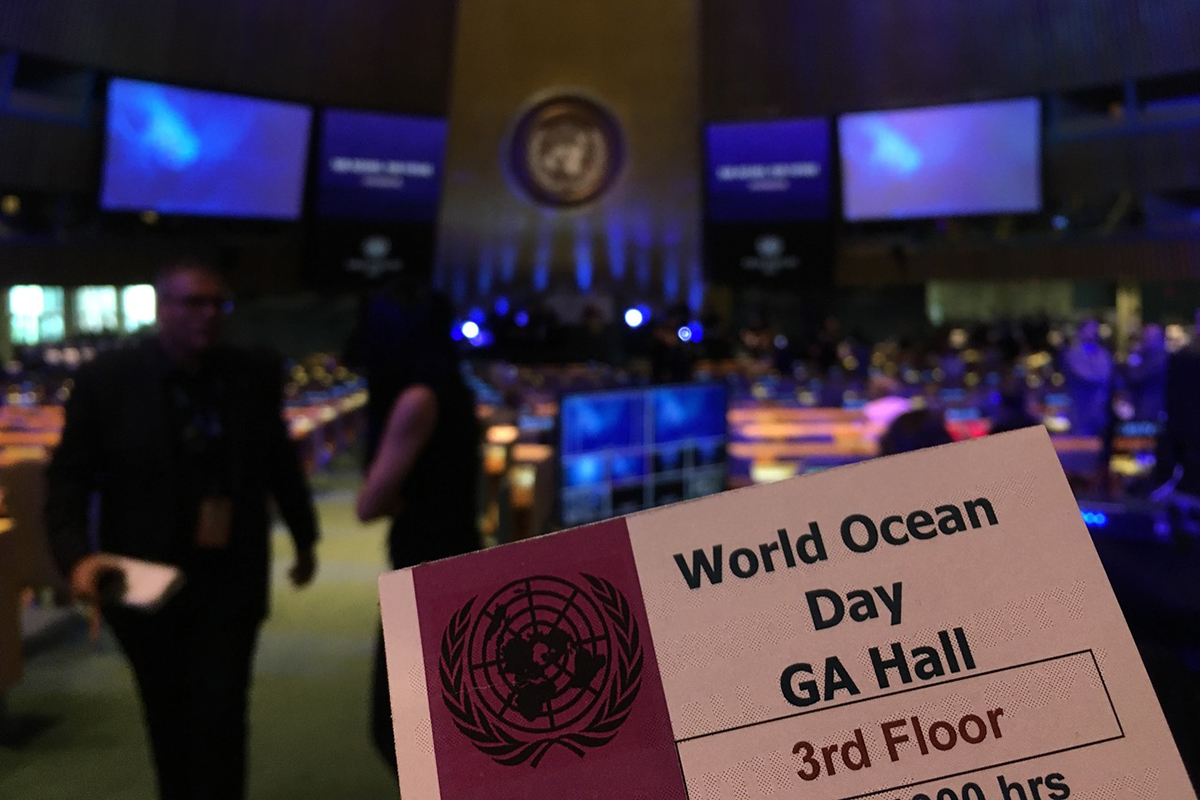

In 2015, the 193 United Nations member countries unanimously adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals seek to ameliorate the universal social and environmental problems facing our planet and include everything from tackling poverty to reducing social and economic inequalities and ensuring a healthy environment. Each SDG has it’s own defined targets and those associated with SDG 14: Life Below Water address the challenges facing marine and aquatic ecosystems, and the people around the world who depend on them. In support of SDG 14, an international Ocean Conference was co-hosted by Sweden and Fiji at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City earlier this month.

As a fisheries scientist who is keenly interested in the intersection between scientific research and policy, I felt lucky to attend the Ocean Conference. Unlike traditional scientific conferences or meetings where researchers present recent findings or collaborate on specific research questions, the Ocean Conference gathered together the UN national delegates as well as NGO representatives, industry members, and business entrepreneurs to present and discuss ways we can independently and collectively tackle the problems affecting the ocean. Illegal fishing, overfishing, marine debris, gender equality, human rights abuses, food security concerns, the impacts of climate change—everything was on the table. As part of this conference came the call for voluntary pledges from the international community on how representatives from all of these sectors will address one or more of these issues.

The week was jam packed with formal meetings in the General Assembly as well as side presentations focused on specific topics. I did my best to attend as many events as possible but, given my research interests and job, made a concerted effort to at least get to the seafood and fisheries discussions. The main takeaways from these were simple in explanation, but will be much harder in execution going forward. Specifically: governments, industry and NGOs need to collaborate more, and the idea of ‘sustainable’ seafood is no longer purely ecology. We need to start addressing all types of concerns in seafood procurement, not just overfishing. (To this end, slavery, illegal fishing, women’s rights, and ending harmful fisheries subsidies were key topics.)

It was much to take in but progress is (hopefully) being made already. Two large-scale voluntary commitments were made by leading fishing industry partners during the conference. Four dozen of the world’s largest tuna companies (producers and distributors), as well as several countries and NGOs all committed to the Tuna 2020 Traceability Declaration, which seeks to ensure complete transparency of tuna products throughout the supply chain. As well, the world’s largest seafood companies committed to the SeaBOS initiative, which outlines specific steps on how they will improve supply chain transparency and traceability. Both of these measures will tackle illegal fishing and seafood fraud.

In total, 1,328 voluntary commitments were put forward by attendees and concerned global organizations. The conference also concluded with the adoption of the ‘Call For Action’ by the UN member countries, a non-binding (and largely symbolic) high-level directive for all countries to adhere to the pledges they have made and to encourage progress to prevent further decline of marine ecosystems. All of this signifies progress. But this is only the first part. As we heard over and over again throughout the week: effective action is needed and it’s needed now.

Fixing the ocean seems like a monumental task—and it is—but we need to start somewhere. And for me, some of the most moving and motivating words I had heard all week came from H.E. Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama of Fiji when he reminded everyone in the General Assembly, “we are not owners, but custodians of our planet”. As humans, we are only one of the millions of species on Earth. Yet, we are the one species whose behaviour impacts all others. So, even if we as ordinary citizens cannot implement a national or international policy, we can still make a difference in our daily lives. We can make a difference by choosing what we eat, drive, buy and do. And if we want a healthy ocean, we all have the power—and responsibility—of choosing to tread on this planet as lightly as we possibly can.

Aquablog post by Laurenne Schiller, Ocean Wise sustainable seafood research analyst & maritime coordinator.

Overfishing is one of the biggest threats to our oceans. With thousands of partner locations across Canada, Ocean Wise makes it easy for consumers to choose sustainable seafood for the long-term health of our oceans. The Ocean Wise symbol next to a seafood item is our assurance of an ocean-friendly seafood choice. www.ocean.org/seafood

Posted June 23, 2017 by Vancouver Aquarium