What does Education mean in Canada’s Arctic?

I recently sat in the living room of Saul Aqslaluk Qirngnirq, listening to stories of how things were and descriptions of how things are for Saul, an Elder in the hamlet of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut. He told me about how he could read the snow and ice, knowing where it was safe to travel and what direction to go regardless of the visibility. “I learned from my dad from long ago to check the ground and the snow all the time,” he said.

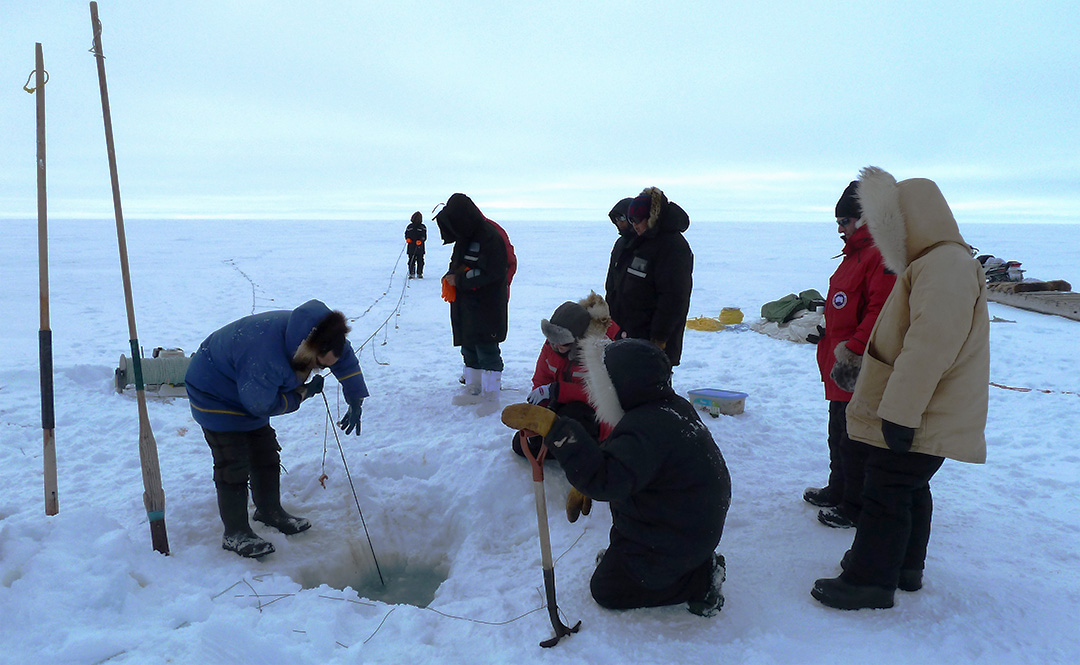

Saul told me how he also used the wind to help him navigate across long expanses of ice. And I know he does this well; I’ve put my life in Saul’s hands on more than one occasion travelling on the sea ice. I have no idea how many times Saul saved my life without me even knowing, with a simple statement like, “Don’t go that way. Go this way.”

On one such trip, Saul had brought along his grandson, Keith. He was excited to be able to pass on some of his knowledge to the younger generation. He told me he is sad and disappointed to see so few young people learning how to travel on the land, to hunt and to get home safely. Saul, like many Elders I’ve spoken to, feels strongly that children need to be learning the traditional ways—the ways that keep people alive in the harsh Arctic environment. They see formal schooling as part of the problem. As Saul says: “Kids are in school and not out on the land.”

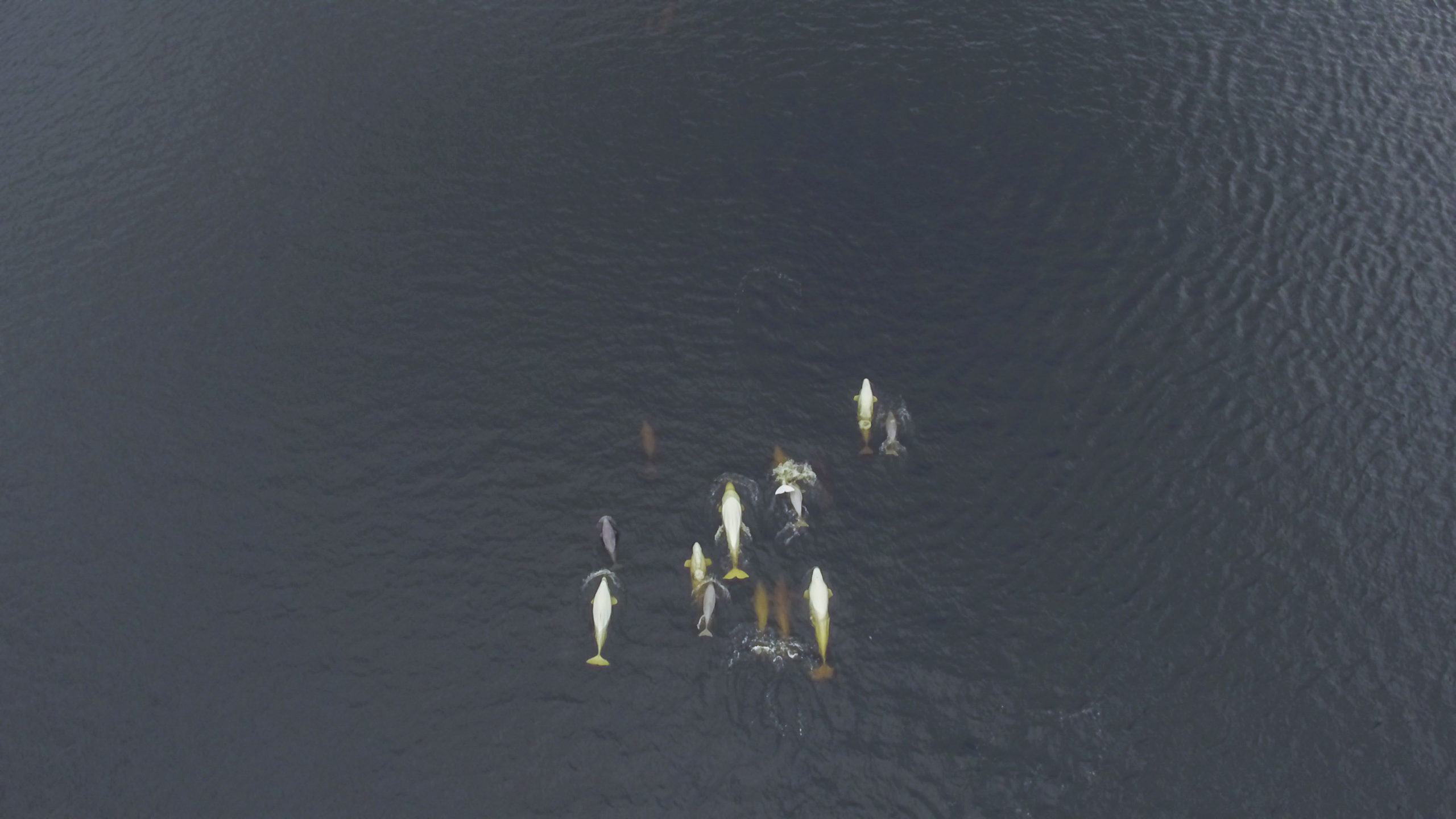

The first time I heard that from an Elder in the North, my instinct was to disagree and to argue about the importance of a good education. I have certainly told many young kids in these communities to stay in school. But it is more complicated than that. It always is. People living in the Arctic do need to learn how to survive on the land, and school is not teaching that. The sea ice is the primary way that people get from one place to another, and travelling safely should be a high priority. And hunting, for so many Inuit is not simply an outdoor pastime: learning to hunt is a matter of food security in the North.

Young people living in Canada’s Arctic communities rarely see any connection between performance in school and the economic or nutritional security of their families. The few jobs available in mining, driving sewage or water trucks or fixing snow machines certainly don’t depend upon completion of high school. And when a father is unemployed or underemployed, a high school diploma won’t feed his family, but good land and hunting skills will.

Young people in Canada’s Arctic—especially young men—are being pulled in two directions: stay in school and get a good education or learn land and hunting skills. For a young man with a family it can be a difficult choice. The truth is the two are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Many young people today are trying to live the “weekend warrior” lifestyle, heading out on Friday evening and returning Sunday night. Many are also getting lost and relying on Elders and other community members to find them and bring them back to safety.

There’s no black and white answer, but somewhere in the grey lie issues of cultural relevance of high school curricula and pedagogical approaches in the North. Perhaps it’s time we stop asking Inuit youth to fit themselves into the current education system and instead ask the system to adapt itself to meet the needs of today’s Inuit youth.

Blog post by Eric Solomon, director of Arctic Connections at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre.

Learn more about issues facing Canada’s Arctic at www.vanaqua.org/ournorth

Posted December 7, 2015 by Public Relations