In Too Deep: The Downside of Deep-Sea Fisheries

What comes to mind when you think of fisheries?

Likely not images of the deepest, darkest places along the ocean floor. Yet, many commercial fisheries operate in these locations, catching deep-sea fish thousands of meters (up to 2000m) deep.

Historically, fish have been caught closer inshore until the early 1970s when a 200-nautical-mile zone (or Exclusive Economic Zone) was established for each country per the United Nations (UN) Law of the Sea, whereby coastal countries have jurisdiction over their marine resources within this zone, and anything beyond is considered international waters, or ‘the high seas’. This reduced access to coastal fishing for foreign fishing fleets, forcing them to resort to alternatives on the high-seas, including the deep sea.

Quick adaption to deep-sea fishing by industrial fleets enabled access to many deep-water fish stocks, and the subsequent exploitation of several. Deep-sea ecosystems are among the most diverse on earth, with many species gathering in great numbers. Yet, these species are largely long-living, slow growing, and late to mature or reproduce, making them more vulnerable to fishing activities and population decline.

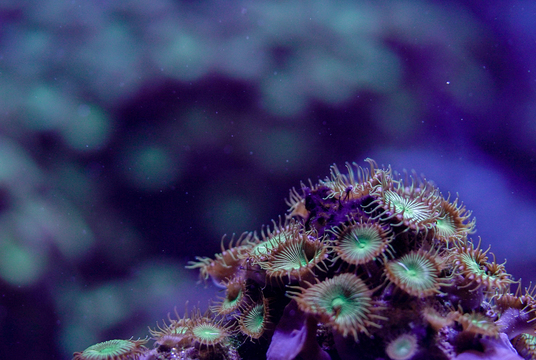

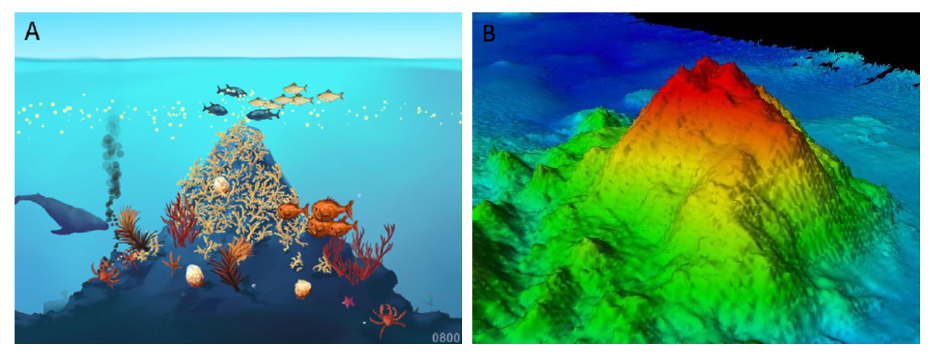

Deep-sea fisheries often operate by targeting topographical features on the ocean floor such as seamounts and mid-ocean ridges where species like to aggregate due to the availability of food and resources. This allows fisheries to harvest large quantities of fish at once, quickly depleting the population. To make matters worse, deep-sea fishing gear can be harmful to deep-water environments, often contacting the bottom (ie., bottom trawls) and destroying precious ecosystems in its path like cold water corals.

Additionally, these gears often accumulate large amounts of unintended bycatch of other vulnerable deep-water species. Management of industrial deep-sea fleets has been ineffective, many of which have fallen into a boom and bust pattern over the years.

An example of a commercially exploited deep-sea fish is orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus). These fish can live to be upwards of 100 years old and do not reach reproductive maturity until they are about 30 years old .

Typical of deep-sea fish, orange roughy gather around continental slopes and seamounts in large numbers, making them easy to target for fishers. This late reproductive cycle and long lifespan means once populations are harvested, recovery is slow.

Orange roughy can only withstand low levels of fishing if populations are to be maintained year over year making them particularly vulnerable to overfishing, which is has occurred through a considerable extent of their range.

Continually, new species are targeted by fisheries to fill the supply gap left by fish whose populations have been decimated due to overfishing. Despite considerable attention to these issues, including management efforts by the UN and the Food and Agricultural Organization to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems targeted by deep-sea fisheries on the high seas, uptake of these measures have been slow and the impact not yet reflected in an uptick in the health of deep-sea stocks.

A UN World Ocean Assessment notes that it could take “centuries to millennia for deep-sea ecosystems to rebound from the impact of bottom trawling”.

Call to Action

Ocean Wise takes the environmental impact of gear type, location, and species into consideration when making recommendations. To ensure your seafood choices are not impacting deep-sea habitats, check to see if the item on your menu is Ocean Wise recommended before you consume.

Aquablog written by Sam Renshaw, Seafood Science Analyst, Ocean Wise Seafood

Additional Academic Resource

Clark, M. R., Althaus, F., Schlacher, T. A., Williams, A., Bowden, D. A., & Rowden, A. A. (2016). The impacts of deep-sea fisheries on benthic communities: A review. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 73(suppl_1), i51–i69. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsv123

Cover: gordodenkoff, Getty Images

Posted October 6, 2021 by Ocean Wise