Just Another Day Collecting Whale Poo

By: Kaitlin Yehle, MSc Student

It’s 6:00am and my phone is buzzing beside my pillow, letting me know it’s time to get ready for another day on the water collecting Northern resident killer whale feces.

I force myself to get up instead of hitting snooze, a difficult feat after several weeks of field work, and walk to the kitchen of our field house in Alert Bay to look out the window over Johnstone Strait. Foggy. Not unusual for an early morning this time of year. At this point in the summer, the morning routine occurs without much chatter. Alex starts the coffee and I hop on the computer to check the marine weather and wind forecasts for the day. The fog should lift mid-morning, and the winds won’t pick up until later afternoon, so the day is looking promising. I check the Orca live community site and there have been no updates since last evening; the hydrophones are quiet except for the low hum of vessels travelling through the Strait. We eat breakfast, pack some lunches for the day, load our equipment into the truck (can’t forget the poop scoops!), and head to the marina.

We make our way east down Johnstone through the morning fog. We wouldn’t even be able to see the whales more than a few hundred meters from us, but with the help of a small hydrophone we often detect killer whale calls (and sometimes echolocation clicks) from more than three nautical miles away. We stop to “drop the pickle” – the field biologists’ term for deploying the hydrophone – and we can hear the white noise of the sea: the cyclical humming of distant vessels and the high-pitched whines of closer speedboats travelling past. These are noisy waters. We don’t fully understand how underwater noise affects killer whales and other marine life (it is a question many scientists are working hard to answer), but listening to the noise for just ten minutes is difficult for me. I turn off the speaker. I can’t imagine not being able to escape from it as easily as I just did.

After a few more “pickle” stops down Johnstone Strait, with the fog starting to lift and no sign of killer whales, we get a text from the photogrammetry crew that they’ve located the A30 matriline off of Bere Point on Malcolm Island. When we arrive on scene, the A30s are spread out in several groups, and the photogrammetry team, aboard Skana, has the drone up over a group of four whales. We get our vessel into position, about 400 metres behind the whales, and quickly set up all our gear so we are ready for a “fecal event.” Now, it’s a waiting game.

While we are hoping for a VHF call from Skana, letting us know they’ve seen defecation from the drone, we are also continuously scanning the water looking for anything that resembles feces that might not have been seen from above. I am always asked, “how do you find killer whale feces, do they float?” The answer is both yes and no. It depends on the sea conditions, and where the whale is in the water column when it defecates. It also likely depends on the diet and composition of the feces. Sometimes we watch as it disperses and sinks away, while other times it floats at the surface for much longer.

Holly Fellowes poised with the poop scoop on the bow, watching Skana with the drone over northern resident killer whales ahead. Credit: Kaitlin Yehle

It’s not long this morning before we get our first call from Skana, letting us know A84 has just defecated! As we carefully approach, I am ready on the bow with the poop scoop – a beaker fastened to a pole. I can see the yellow cloud lingering in the water, but the fragments are very small and sinking quickly. We’re frantically scanning the surface for any pieces we might be able to collect, but this one has gotten away from us, and my stomach sinks with the scat.

A few hours later with a different group of killer whales, when we have nearly given up hope for today, we get another chance. Skana comes over VHF again: “Go for gold!” Not wanting to watch another sample sink away, it takes everything in us to calmly maneuver the boat through the water instead of racing over to the area. A slow, drifting approach, though, is the only way we’re going to spot and collect the feces. This time, we find ourselves surrounded by floating pieces and an overwhelming fishy odour in the air. Jackpot! Alex puts the vessel in neutral and we both get to work scooping up the poop.

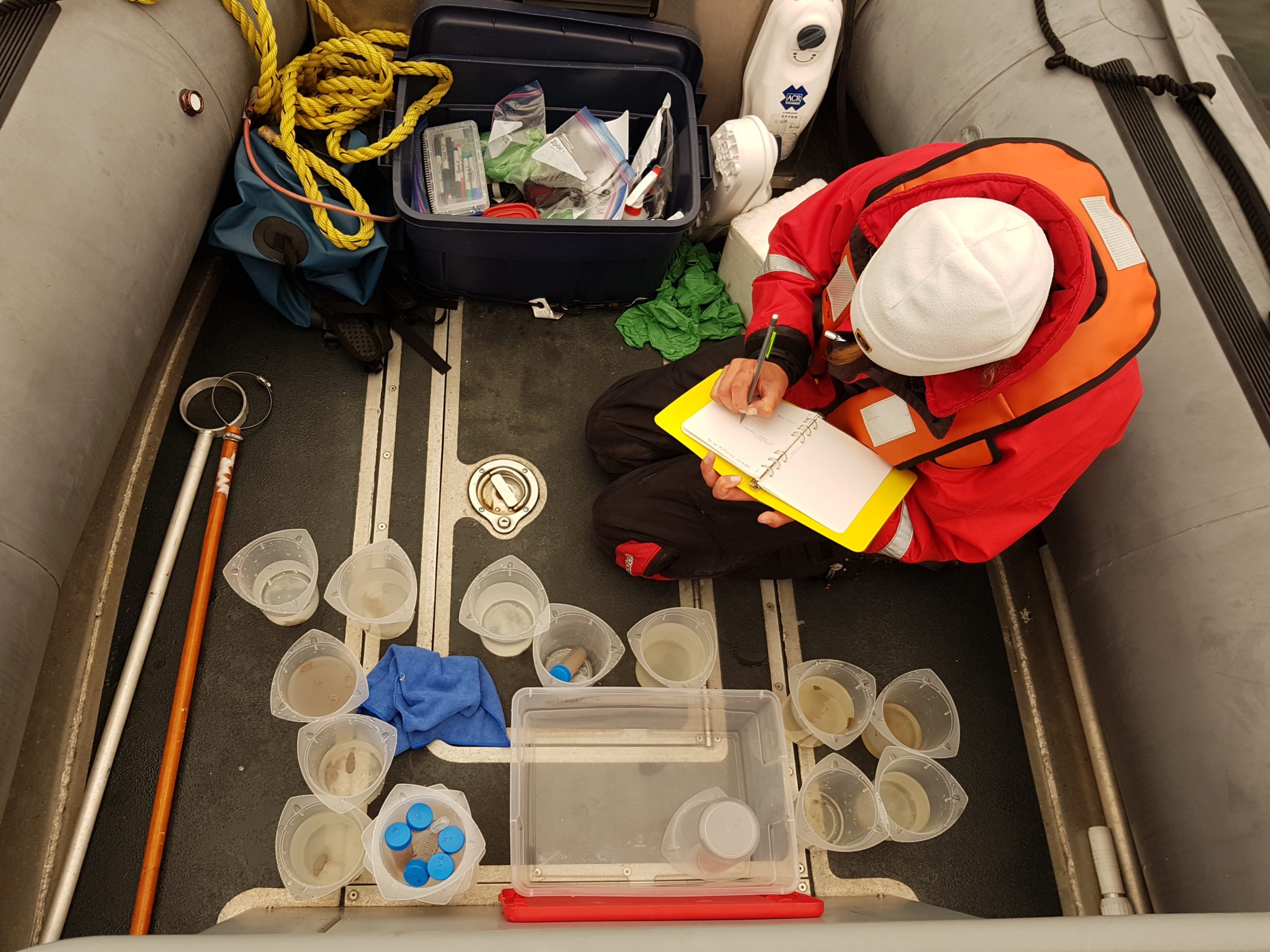

We record some notes about the physical appearance of the sample: its colour, odour, apparent texture, and buoyancy. In this case: green-brown, fishy (and slightly putrid as Alex wrinkled his nose in disgust), lots of mucous, and mostly floating. We carefully pour feces from the beakers into smaller tubes, and centrifuge the tubes for five minutes to separate and pour out as much seawater as possible. We take a swab of the sample for the Ocean Wise Conservation Genetics team, who will determine the individual from which it came using DNA in the feces, and then freeze the fecal sample in a dry ice cooler we have on board.

By the time we are done, we’re trailing the whales by about a kilometer and the wind is starting to pick up as predicted, which makes collecting feces more difficult. We decide to call it a day. A pretty successful day at that… or, as we like to say, a pretty “shitty” day!

Back in Alert Bay we unload, clean, and charge all of our gear, store the prized fecal sample, and complete the daily data entry on the computer. Alex makes dinner while I clean, disinfect, and sterilize the beakers we used today, so they are ready for tomorrow when we do this all over again.

Each summer since 2018, we spend roughly six on the west coast of Vancouver Island collecting feces from the Southern resident killer whales, in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada studies, followed by three weeks here collecting feces from the Northern residents. 2020 is our final year of fecal sampling, and with three years of samples from both populations, we aim to better understand factors affecting their health, stress, and nutrition.

Read more about how we use feces to assess health, stress and nutrition here.

Ocean Wise’s fecal hormone study is part of a collaborative project with Fisheries and Ocean’s Canada (DFO) and is funded by DFO’s Oceans Protection Plan.

Posted August 4, 2020 by Sarah Wilson