Monitoring killer whale body condition amidst a pandemic

By: Amy Rowley, Photogrammetry Research Assistant

This summer, Ocean Wise’s photogrammetry team were lucky enough to return to Johnstone Strait to continue our fieldwork to monitor the body condition of northern resident killer whales using unmanned aerial vehicles (commonly known as drones). After an uncertain start to the year due to travel restrictions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, our team was thrilled to be out of our home offices and back in the field.

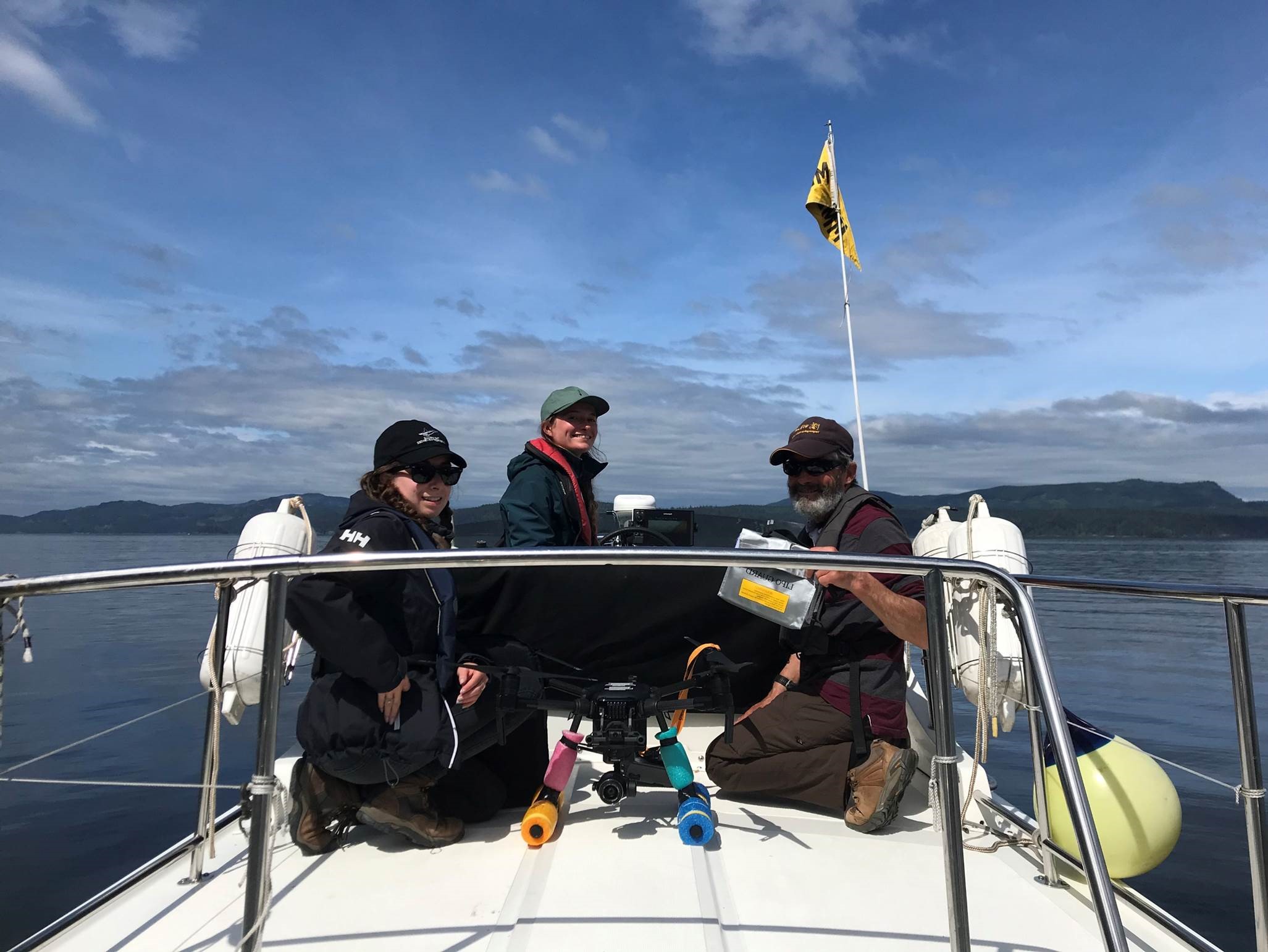

Armed with masks, thermometers and a comprehensive COVID-19 safety plan, our team of three arrived in Alert Bay in early August with Ocean Wise’s research vessel Skana. As in previous years, Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard led the team as principal investigator and drone pilot. He was joined this year by some new field recruits as Brittany Visona, the drone camera operator for the last two years, had skipped the start of the field season to attend her wedding (pfft what an excuse!). Luckily, Karina Dracott, acting manager of the Ocean Wise’s North Coast Cetacean Research Initiative based in Prince Rupert, was able to step in as camera operator and I took the role of vessel operator-in-training. After a few days of test flights on land to get back in the swing of things and troubleshoot some technical hiccups, we were ready to get out on the water and start taking aerial photos of killer whales.

Our days in the field start early, typically waking up around 6:00 am to check the weather forecast and conduct the all-important ‘look out of the window’ test. While the rest of the team are hardy west coasters who laugh in the face of inclement weather, our research drone ‘Auklet’ is a bit more sensitive to wind and rain. If the visibility and wind conditions look promising – or at least passable – we guzzle coffee, grab our equipment and aim to be at the dock by 7:00 am.

Killer whales range over huge distances and can travel hundreds of kilometres in a single day. This means that even if we saw them the day before, they’re very unlikely to be in the same place, so usually some searching is required. We use a number of techniques to find whales, such as scanning the water for blows or for fins breaking the surface, using a hydrophone to listen for their calls, and communicating with friends and colleagues in the area – like Ocean Wise’s fecal team who were also able to conduct their annual fieldwork collecting resident killer whale poop samples in Johnstone Strait. Sometimes it seems like the water is teeming with life with whales in every direction, and other times we can go for days without spotting a single dorsal fin.

However, the excitement of finding whales never gets old! Once we locate a group and have a sense of the approximate number of individuals, their direction and their spatial distribution, the first step is to identify exactly which whales are present. Our research currently focuses on northern resident killer whales, a fish-eating population that numbers around 300 individuals and ranges from southern Alaska to northern Vancouver Island. We also opportunistically photograph Bigg’s (also known as transient) killer whales, a distinct population (or ‘ecotype’) that feeds on marine mammals and spans the entire western North American coast. The photogrammetry project aims to monitor killer whale body condition over time, and therefore requires repeat images of the same individuals to be taken in successive years. This makes it important to identify each whale, which we do by examining scars, notches and other markings in the dorsal fins and saddle patches either in the field or from photographs.

Once we have identified which whales we are with, it’s time to launch the drone! Launching an unmanned aircraft from a small crowded boat can be challenging. The camera operator (Brittany or Karina) holds the drone high above her head and drone pilot Lance flies vertically to a safe height of 30m before heading in the direction of the whales. While the camera operator focuses on the image feed, directing the pilot to stay above the whales, the pilot and vessel operator keep an eye on the drone and look for whales on the surface while following at a slow speed and a distance of at least 200m. For our photogrammetric measurements, the camera must be directly above the whales as they surface, with their bodies as straight as possible. Sometimes this works perfectly, and sometimes…. the whales have other ideas.

Each flight lasts approximately 25 minutes before the batteries run low and Lance skillfully pilots the drone back to the boat for Brittany or Karina to catch. Once Auklet is safely back on board, the team springs into action charging batteries, replacing SD cards and preparing to launch again. We can complete as many as 12 flights per day, depending on conditions and the number of whales we find. Over the course of the 40-day field season, we logged 112 flights over 80 northern resident killer whales and 25 Bigg’s killer whales.

We returned to Vancouver in September, tired but keen to sort through the data we collected and begin the long and meticulous process of measuring the whales captured in the photos over the winter. Of the tens of thousands of aerial images taken over the course of the field season, only a thousand or so will meet the standard for measurement. Body condition is measured by examining the ‘eyepatch ratio’ – essentially the difference between the distance between eyepatches at the anterior tip and ¾ of the way down the eyepatch. This provides a measure of post-cranial fatness, which is an indicator of nutritional stress. Using this method allows us to monitor body condition non-invasively with minimal disturbance to the whales, with the ultimate goal of assessing how fluctuations in salmon abundance influence whale condition in order to inform fisheries management.

Reflecting on my first field season with the photogrammetry team, I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to ditch my desk for a while and experience the ecosystems our work aims to protect. After the strange same-ness of life amidst a pandemic, going to work every morning with no idea what exotic matrilines, exciting behaviours or freak engine trouble awaited us was like a cool north island rain shower for the soul. While the experience was certainly a big learning curve and challenging at times, getting to spend this time in the field with my colleagues was the highlight of an unusual summer. The whole team are grateful for the opportunity to continue our work in these altered circumstances and look forward to sharing the findings with you!

Ocean Wise’s photogrammetry study is funded in part by Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Oceans Protection Plan, the Canada Nature Fund, LNG Canada, and the Wild Killer Whale Adoption Program. Fieldwork was conducted under DFO permit MML18.

Posted November 19, 2020 by Marine Mammal Research