Five Awesome Facts You Didn’t Know About Echinoderms

So, you think you know everything there is to know about echinoderms? Echinoderms are the group of animals that includes sea stars, urchins, sea cucumbers, feather stars and brittle stars, and they are the only group of animals that is exclusively marine. Yes, yes, you likely already recognize the common features of echinoderms: their body structure is characterized by “pentaradial” symmetry – their body can be divided into five, similar-looking, circularly-organized components. Echinoderms have no heart, brain or eyes; they move their bodies with a unique hydraulic system called the water vascular system.

But now you’d like to learn something new. Something awesome. Well, you’re in luck.

At the end of May, I had the privilege of representing the Vancouver Aquarium’s Coastal Ocean Research Institute and Simon Fraser University at the 15th International Echinoderm Conference in Playa del Carmen, Mexico, showcasing some of the research we’re doing on sea stars and sea urchins. The International Echinoderm Conference meets once every three years to discuss all matters echinoderm. Specialists ranging from geneticists and taxonomists to climate scientists and biotechnology researchers present their latest echinoderm-related research and receive feedback from their peers. This year saw almost 300 participants from around the globe. As an ecologist, it was truly a fantastic learning experience to hear from such a diverse group of researchers. In honour of pentaradial symmetry, here are five of the many great things I learned:

- Sea cucumbers are delicious: That’s right – you can eat these things. And not only can you eat them, but millions of people all over the world want to eat them. Sea cucumbers have become a lucrative international fishery. It’s the five longitudinal muscles that run the length of the animal that people eat. Dried, breaded, or fried; depending who you ask it tastes like either scallops or calamari. Like any fishing industry however, care needs to be taken to ensure the stocks don’t become depleted.

- Sea cucumbers actually mitigate climate change: Maria Byrne from the University of Sydney discussed the effects of climate change on echinoderm life stages. Sea cucumbers eat sediment, filtering out algae and microbes, and their resulting excrement produces sediment that is higher in pH (less acidic), combating ocean acidification. That’s right; sea cucumber poop mitigates ocean acidification! So like all species, sea cucumbers play an important role in the ecosystem.

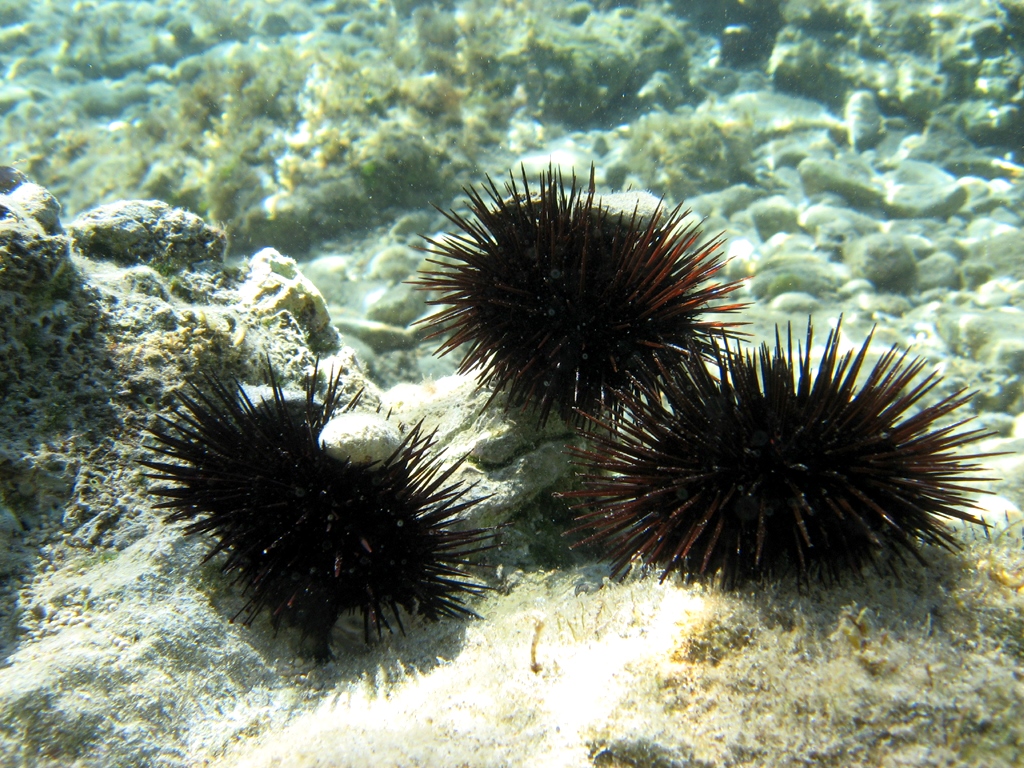

- Urchins eat rock: Have you ever looked in a tide pool and seen urchins nestled right into the stone? Dr. Michael Russell from Villanova University has. In his words, the research he presented at the conference was motivated by, “A child-like curiosity when you put your head in a tide pool and ask, ‘Did urchins build those holes? How long did it take?’” He found that urchins dig their own personalized holes in the rock with their teeth, and probably stay in the same hole for their whole lives. In the process they ingest some of the rock. Not only do they ingest it like the sea cucumber, but they can actually draw nutritional value from the rock itself.

- Urchins move at the speed of … smell? A type of urchin called a heart urchin can bury in the sediment, and using smell is able to dig itself away from predators. Masaya Saitoh from Kanagawa University found that larger urchins were more successful at escaping, and thinks that this response may have driven urchin evolution towards larger body size. Urchins also use smell, or “chemoreception,” to find food. Using time-lapse photography, Katie MacGregor from Laval University found that green urchins can detect and aggregate on kelp in as little as three hours. This is a lot more impressive when you remember that urchins have no brain or eyes! This gives rise to another cool fact about urchins: they form growth rings in their skeletons, much the same way as trees form seasonal rings. However the rings in urchins aren’t necessarily seasonal because they can change with food availability or environmental conditions.

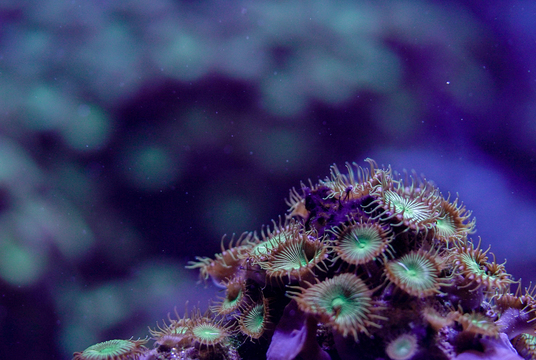

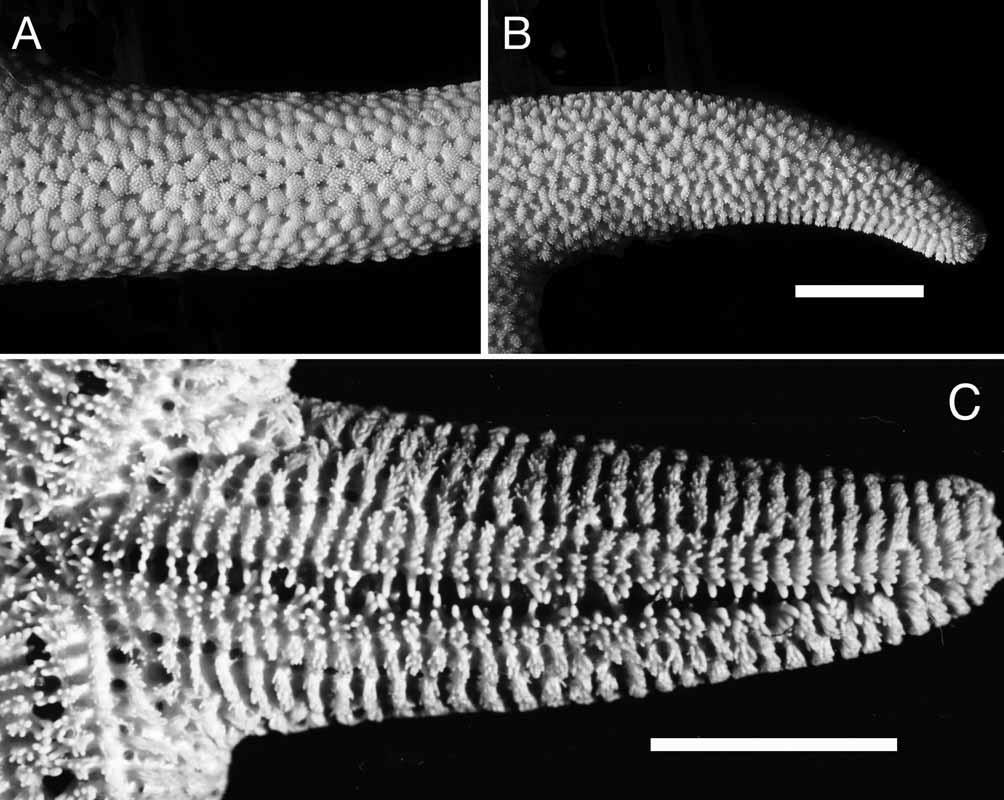

Sea urchins can congregate relatively quickly on a food source. - We still have an incredible amount to learn about echinoderms: Although it’s easy to think of sea stars as one of the most iconic and easily recognized animals on the beach, researchers are discovering new species all the time. In some cases, genetic technology is allowing us to take a closer look than ever before. One example is the blood star, Henricia leviuscula, previously thought to inhabit waters from California to Alaska. Dr. Doug Eernisse from California State University Fullerton is now finding that there are more than 20 species of blood stars, all with very specific geographic ranges. Different species are often distinguishable only by very tiny differences in their skeletal structure. In other cases, researchers are discovering new species simply because no one has ever looked before. Dr. Stephen Jewett and his team from the University of Alaska Fairbanks recently embarked on the first ever study to document sea stars in the Aleutian Archipelago. Of the 63 species documented, 22 are known only to that area, and 18 were newly discovered. Their discoveries are revealing new information about the evolutionary history of life in the sea. Just one of many reasons why studying echinoderms is so exciting!

Species from the blood star group can look identical from afar, but be entirely different species.

Blog post by Jessica Schultz, research coorindator for the Howe Sound Research Program at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre.

Posted July 2, 2015 by Vancouver Aquarium