Can Whales Mitigate Climate Change? Whales and the Carbon Cycle

By: Kaitlin Yehle, MSc Student

The skies of metro Vancouver have been an orange haze for much of September; smoke from wildfires to the south, in Washington, Oregon and California, sitting heavy in the air. For me, it’s a tickle at the back of my throat, but I am privileged to be one of those least affected by the dire air quality – which reached among the worst in the world for a few days earlier this month. For those with underlying health conditions and without safe, indoor space it is a much more serious threat. And for those who have lost their homes, loved ones, and lives to the fires, it is devastating.

Climate change is happening. It’s here, it’s now, it’s all around us. Look out your window. The smoke may have cleared, but the carbon released from the burned forests into the atmosphere is only accelerating the change.

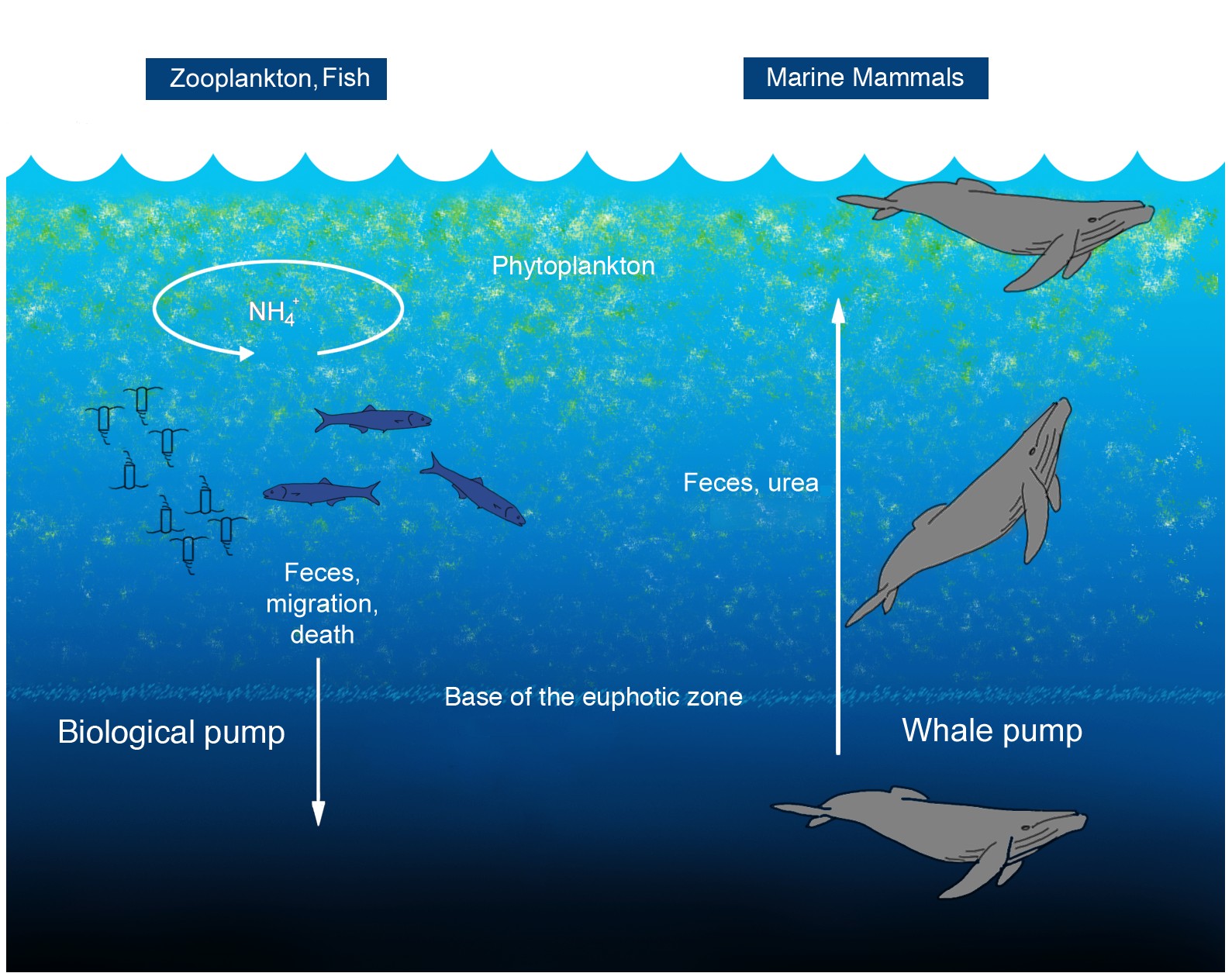

Climate change is accelerated by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities, like burning fossil fuels and deforestation, which release stored carbon into the atmosphere. The ocean, which is likewise threatened by climate change, is an important reservoir of atmospheric carbon – also known as a carbon sink. Through biological and physical processes, carbon at the surface is removed from the air and moved deeper into the seafloor for long-term storage – a process coined “the ocean carbon pump.” You may be familiar with carbon storage and the ocean carbon pump, but do you know how whales contribute to it?

Whales lift nutrients from deeper water to the surface during diving ascents, and those nutrients enable phytoplankton – the instigators of carbon uptake – to flourish. Sperm whales and Cuvier’s beaked whales are some of the deepest divers in the world, with recorded dive depths between 2000 and 3000m!1 Adding to this upward pump, whales tend to feed at depth (taking in nutrients), but defecate near the surface – releasing large volumes of waste rich with nitrogen and iron, which are often the limiting nutrients for phytoplankton growth.2 Through this “whale pump,” whale poo (my favourite topic!) plays an important role in carbon sequestration. Rich in iron, sperm whale feces alone might move hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon from the atmosphere to the deep ocean by promoting plankton growth.3,4

Even in death, whales continue to contribute to carbon storage; their carcasses sink to the ocean floor taking all the carbon that has accumulated in their body over their life with them – the ultimate sacrifice! As some of the largest marine mammals (think of blue whales) with life spans over decades, their carbon accumulation is comparable to that of large trees.5

But just how much do whales contribute to carbon uptake in the ocean? It’s a difficult question to tackle, but it is not insignificant. Whale carcasses alone move an estimated 30,000 tons of carbon per year to the deep sea,5 and that’s just one piece of the puzzle. Perhaps what’s more striking is that this number used to be much higher. Industrial whaling decimated baleen whale populations around the world – to less than 25% of pre-whaling numbers – removing an estimated total of 17 million tons of carbon (stored in whales!) from the ocean.5

Is it all doom and gloom, as I look out the window at the smokey sky? I hope not. Many whale populations have been recovering since the ban on commercial whaling in 1986, showing that our actions can help. Restoring whale populations could greatly increase ocean carbon storage again, and may be as effective as reforestation projects and ocean iron fertilization, with the potential to remove an additional 160,000 tons of carbon per year from the atmosphere.5 Unfortunately, whales continue to face new threats in our changing oceans – warmer waters and ocean acidification are direct results of climate change. If we want to see flourishing whale populations again, we must also work to reduce our carbon output on a large scale. And quickly, we’re running out of time.

References & Recommended Reading:

1Schorr GS, Falcone EA, Moretti DJ, Andrews RD (2014) First Long-Term Behavioral Records from Cuvier’s Beaked Whales (Ziphius cavirostris) Reveal Record-Breaking Dives. PLoS ONE 9(3): e92633. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092633

2Roman J, McCarthy JJ (2010) The Whale Pump: Marine Mammals Enhance Primary Productivity in a Coastal Basin. PLoS ONE 5(10): e13255. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013255

3Roman J, Estes JA, Morissette L, Smith C, Costa D, McCarthy J, Nation JB, Nicol S, Pershing A, Smetacek V (2014) Whales as marine ecosystem engineers. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12(7): 377-385. https://doi.org/10.1890/130220

4Lavery TJ, Roudnew B, Gill P, Seymour J, Seuront, L, Johnson G, Mitchell JG, Smetacek V (2010) Iron defecation by sperm whales stimulates carbon export in the Southern Ocean. Proc R Soc B 277: 3527–31. http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.08635Pershing AJ, Christensen LB, Record NR, Sherwood GD, Stetson PB (2010) The Impact of Whaling on the Ocean Carbon Cycle: Why Bigger Was Better. PLoS ONE 5(8): e12444. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012444

Posted September 30, 2020 by Marine Mammal Research