Tracking Contaminants in Killer Whale Habitats

By: Joseph Kim, Research Scientist

Contaminants in coastal British Columbia (BC)

It is late at night and I notice that more data have been uploaded to the PollutionTracker database. I am using these data to look at contaminant levels within and around killer whale critical habitat (areas where killer whales spend a large proportion of their time). These data are helping us better understand which contaminants killer whales and other marine organisms are being exposed to and possible health effects.

The PollutionTracker program was established by Ocean Wise in 2015 to determine and monitor marine pollution in coastal BC. The PollutionTracker database stores tens of thousands of data records for contaminants of concern to ocean health. Data are grouped into fourteen general contaminant classes, including pharmaceuticals and personal care products, flame retardants, pesticides, heavy metals, and petrochemicals, which have been detected in sediment and mussels collected from sites along the BC coast.

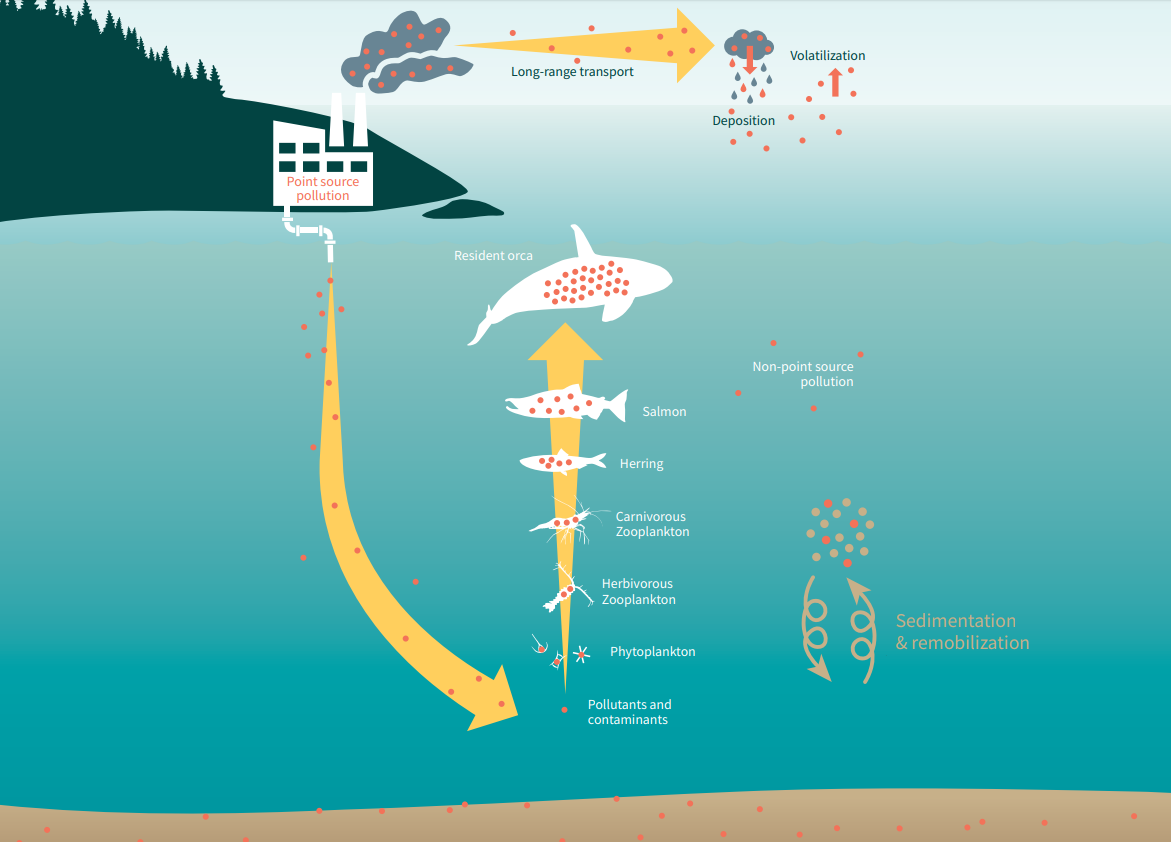

Most of these contaminants are of human origin and have the potential to harm marine mammals. They can work their way up through the food chain by the processes of “bioaccumulation” and “biomagnification”.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: What do they mean for Killer Whales?

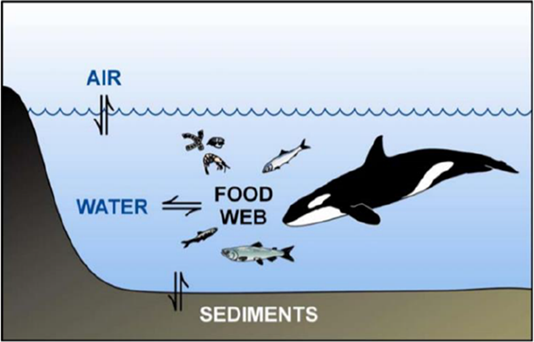

Bioaccumulation is the process by which contaminants enter the food web, passing from the environment or food to individual organisms and building up in their tissues. This occurs when organisms cannot get rid of contaminants through excretion (some contaminants can be excreted, depending on their chemical properties and the organism). Biomagnification occurs when contaminants are passed from one level of the food chain to the next, increasing in concentration with each level. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification are two distinct processes that often occur in concert with one another.

Typically, contaminants enter and concentrate at the base of a food web, within photosynthetic organisms like phytoplankton. Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton and in turn accumulate contaminants at a higher concentration. Many zooplankton are eaten by small fish, which are then eaten by larger fish, and contaminant concentrations continue to bioaccumulate and biomagnify. Eventually, contaminants are passed from prey to the top predators of the marine food chain (killer whales), resulting in the highest levels of contaminants.

The most dangerous and toxic types of contaminants found in killer whales belong to a group called Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). POPs are notorious for their long-range transport and persistence in the environment, and some of the most well-known POPs include pesticides such as Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), flame retardant chemicals known as Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs), and pervasive industrial chemical contaminants such as Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). POPs are of particular concern in killer whales because they bioaccumulate in fatty tissues (blubber) and have negative health effects, such as reproductive impairment, suppression of the immune system, and disruption of the endocrine (hormone) system (Buckman et al. 2011; Mos et al. 2006; Ross 2006).

The threat to killer whales from POP exposure is evident from PCBs alone. Studies have shown extremely high levels of PCBs within the blubber of BC’s killer whales, making them “among the world’s most PCB-contaminated marine mammals” (Ross et al. 2000).

With growing evidence that BC killer whales are vulnerable to food web bioaccumulation of POPs, and given their current status as either “threatened” (northern residents and Bigg’s killer whales) or “endangered” (southern residents) under the Species At Risk Act (SARA) in Canada, strict regulations for the assessment and management of contaminants should be put in place to conserve killer whale critical habitat.

Sediment Monitoring and Guidelines

Contaminants move after entering the marine environment (Figure 2), and sediment has been shown to be both a place of “storage” and a subsequent “source” of contaminants, making it an important component of marine contaminant monitoring. Through deposition and resuspension of sediment, contaminants are stored and remobilized, respectively, re-exposing aquatic organisms.

Sediment Quality Guidelines (SQGs) are a regulatory tool available for the assessment and management of contaminants in aquatic environments. SQGs represent the maximum concentration of a contaminant, or class of contaminants, in sediment below which adverse health effects are unlikely to occur in marine organisms.

In the context of killer whales, SQGs can be used to evaluate contaminant levels in sediment in killer whale critical habitat and provide an indication of potential risks. Therefore, information about contaminants in sediment and the development and use of appropriate SQGs are critical in supporting killer whale conservation efforts.

As a research scientist and data analyst at Ocean Wise, I am using the PollutionTracker contaminant data to conduct a more detailed assessment of killer whale critical habitat quality. This is being carried out by generating maps that show sediment contaminant levels in and around killer whale critical habitat and comparing concentrations to available marine SQGs.

This project is funded in part by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Mitacs Accelerate Program.

References:

Alava, J.J. and Gobas, F.A.P.C. 2016. Modeling 137Cs bioaccumulation in the salmon–resident killer whale food web of the Northeastern Pacific following the Fukushima Nuclear Accident. Science of The Total Environment, 544, 56–67

Buckman, A.H., Veldhoen, N., Ellis, G., Ford, J.K.B., Helbing, C.C., Ross, P.S. 2011. PCB-Associated Changes in mRNA Expression in Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) from the NE Pacific Ocean Environmental Science and Technology, 45(23), 10194– 10202

Mos, L., Morsey, B., Jeffries, S.J. 2006 Chemical and biological pollution contribute to the immunological profiles of free-ranging harbour seals. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 25, 3110–3117

Miller, A., Braig, S., Delisle, K., Ross, P.S. 2020. Pollution hotspots in killer whale habitat pinpointed by new conservation tool. Ocean Watch Spotlight. Ocean Wise Conservation Association, Vancouver, Canada. 22 pg.

Ross, P.S., Ellis, G.M., Ikonomou, M.G., Barrett-Lennard, L.G., Addison, R.F. 2000. High PCB concentrations in free-ranging Pacific killer whales, Orcinus orca: effects of age, sex and dietary preference. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 40, 504–515

Ross P.S. 2006. Fireproof killer whales (Orcinus orca): flame retardant chemicals and the conservation imperative in the charismatic icon of British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 63, 224–34

Posted August 20, 2020 by Sarah Wilson