Orca Awareness Month – answering your burning killer whale questions!

Did you know that June is Orca Awareness month? We love answering your questions about killer whales! Here are a few of the most popular questions we are asked on social media and at outreach events:

Why are orcas called killer whales?

When we are asked this question, it’s usually followed by statements such as: “I don’t think it’s right to call them killer whales” or “don’t you think it demonizes them?”. Simply put, however, killer whales kill and are apex predators of the ocean. Killer whales get their common name from early observations made by whalers and fishermen of these iconic animals hunting other large marine animals. The names used by various cultures throughout history all reflect awe and, in some cases, fear of these magnificent creatures. For example:

- Speckhogger (Norwegian), meaning blubber chopper;

- Baleia Assassina (Portuguese), meaning assassin whale;

- Mörderwal (German), meaning murder whale;

- Polossatik (Aleut), meaning the feared one

Even the name “Orca” which comes from their scientific name Orcinus orca, means “from the underworld” or “demon”.

For more, check out the video featuring our very own killer whale expert, Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard in this article by CBC.

Why do killer whale populations have different food preferences?

It’s all about competition – probably. The British scholar Malthus pointed out 200 years ago that all populations have the capacity to grow until they run out of resources. Competition for resources is a fact of life, and the most successful individuals are either the best competitors…or they’ve figured out ways to escape or lessen competition. Killer whale populations have different histories and are likely to have somewhat different dietary preferences just by chance. Dr. Barrett-Lennard believes that when their ranges overlap, their dietary preferences likely diverge further to reduce competition—a phenomenon called niche partitioning that we see in many other species. In other species, however, we believe that niche partitioning evolves genetically, whereas dietary separation in killer whales almost certainly develops and is maintained culturally. This is possible because whale calves, like baby humans, learn their dietary preferences from their families and social groups. Co-existing fish-eating and mammal-eating killer whales probably don’t know that they have pushed each other into different ecological niches, but they likely do know that there’s no dietary overlap and no reason for conflict over food.

Why don’t resident killer whales just eat other fish or marine mammals if there aren’t enough Chinook salmon?

To answer this question we need to provide some context. There are three ecotypes or forms of killer whales found in British Columbia – residents, which feed primarily on salmon, and more specifically Chinook salmon, Bigg’s (or transients) which feed on other marine mammal species, and offshores which feed on fish species, including sharks. Given that Chinook salmon numbers have dwindled so significantly and resident killer whales are, in some years at least, nutritionally challenged we are often asked why a resident killer whale couldn’t just eat a seal. While there is nothing about a resident killer whale’s biology to prevent it from snacking on a tasty seal, this is where learned skills and culture come into play. For the reasons outlined in the previous question, Chinook salmon are part of resident killer whale culture, while seals are not. Killer whales live in matrilineal families, meaning that they are structured around mothers. Young killer whales are taught skills by their mothers and grandmothers, and one of these skills is how to forage for and eat Chinook salmon. If by remote chance a resident killer whale were to choose to forgo its culture and try a seal, it wouldn’t find it easy—hunting seals requires an entirely different set of tactics!

How do we know which killer whale is which?

In the 1970s, pioneer killer whale researcher, Dr. Michael Bigg and his colleagues realized that individual killer whales could be recognized from nicks and scars, and by the shape of their dorsal find and saddle patches. Since then, photo-identification catalogues have been published, with each individual killer whale assigned a distinct alpha-numeric designator. Resident killer whales are censused annually in B.C., with most individuals accounted for. Their tight family-based social structure makes this job easier – if a known individual is missing from its family in more than a couple of encounters it can be reliably considered dead. Censusing Bigg’s is a little more difficult because they have a larger range and somewhat more dynamic social structure, and offshores are rarely seen by coastal researchers and are even more challenging to census.

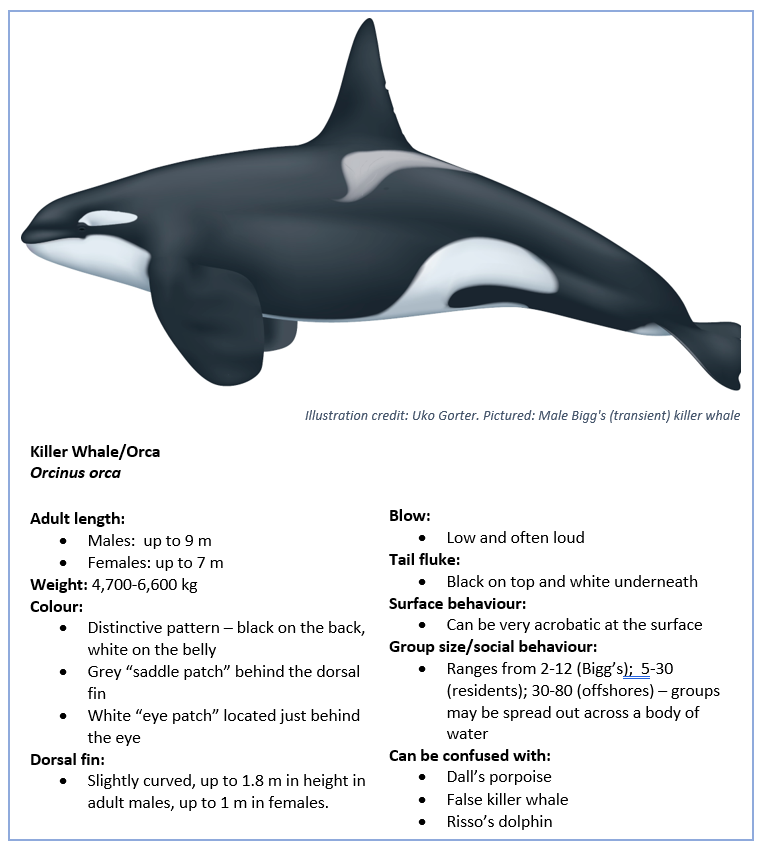

How can you tell male and female killer whales apart?

Killer whales are sexually dimorphic, meaning the males and females look different at maturity. Males may reach 9 m while females are smaller at 7 m. While all juvenile killer whales have small, curved dorsal fins for the first decade of their life, male killer whales “sprout” a tall, triangular dorsal fin that can reach up to 1.8 meters in height as they mature! Females retain a smaller, more curved dorsal fin throughout their lives. Adult males have much larger pectoral fins and the tips of their tail flukes curve downwards. Male and female killer whales also have different pigment patterns on their undersides which can be particularly helpful for sexing calves. Calves frequently roll over and expose their bellies while playing, giving sharp-eyed researchers a chance to distinguish boys from girls.

How long do killer whales live?

Killer whales are long-lived animals. Mortality in the first six months is high, but the life expectancy of females that make it through that period is approximately 50 years. That said, a good many make it into their 80’s, and one, a southern resident killer whale known as Granny (J2) was estimated by some researchers to be 105 years old when she died in 2016. In contrast, six month-old males have a life expectancy of about 30 years although a few live into their 50’s.

For answers to any other burning questions and for more information on killer whales and our research, make sure to check out killerwhale.org.

Wondering what you can do to help killer whales in British Columbia?

- Adopt a Whale – Symbolically adopt a killer whale and help support conservation research on wild killer whale populations in B.C. Learn more about the Wild Killer Whale Adoption Program at www.killerwhale.org.

- Participate in Citizen Science – Report your whale sightings using the WhaleReport app. Sightings give valuable information about species distribution patterns and helps in recovery and management planning.

- Give them space – Make sure to always follow the Be Whale Wise Guidelines when watching whales, or visit Whale Trail BC locations and observe whales from land – a zero-impact alternative to whale watching.

- Eat sustainable seafood – Know if your seafood is from a healthy, stable stock caught by environmentally friendly methods. Choose Ocean Wise Sustainable Seafood.

- Dispose of waste responsibly – What goes down your drain eventually ends up in the ocean. Dispose of your hazardous waste at designated drop-off sites. Always reduce, reuse, and recycle.

- Clean our shorelines – Garbage in the ocean poses a risk to all marine life, including killer whales and their prey. Help reduce marine debris by participating in the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup.

Posted July 6, 2020 by Ocean Wise