Killer Whale Culture: From Matrilines to Mating Rituals

With the recent flux of summer killer whale sightings in B.C., I’ve often been asked, “Why do we always see killer whales travelling in groups? Are these breeding groups, families, or just random congregations of whales that happen to be at the same place at the same time?”

After humans, killer whales have some of the most complex cultures and social structures of any species on the planet. Resident killer whales, or “fish-eaters” are among the best understood ecotype of Orcinus orca in B.C. There are two population that live in our waters, northern and southern residents, and they are completely distinct from one another. Though their habitat ranges have an overlap, their genetics, behaviour, and language differ. The two populations are rarely seen in close proximity and don’t appear to interact.

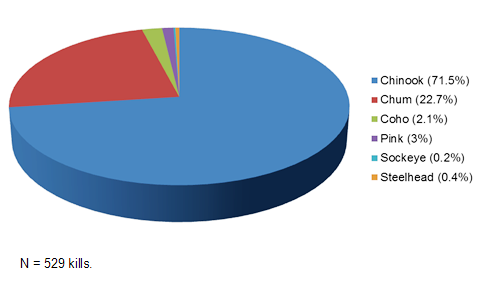

Both northern and southern resident killer whales prey primarily on salmon, chinook salmon, in particular. In years of poor chinook abundance their pickiness can be a significant threat, particularly for calves and pregnant mothers where malnutrition plays a large role in mortality. In a given year, chinook abundance seems to have a strong correlation with killer whale mortality in the year.

Mom’s the Word

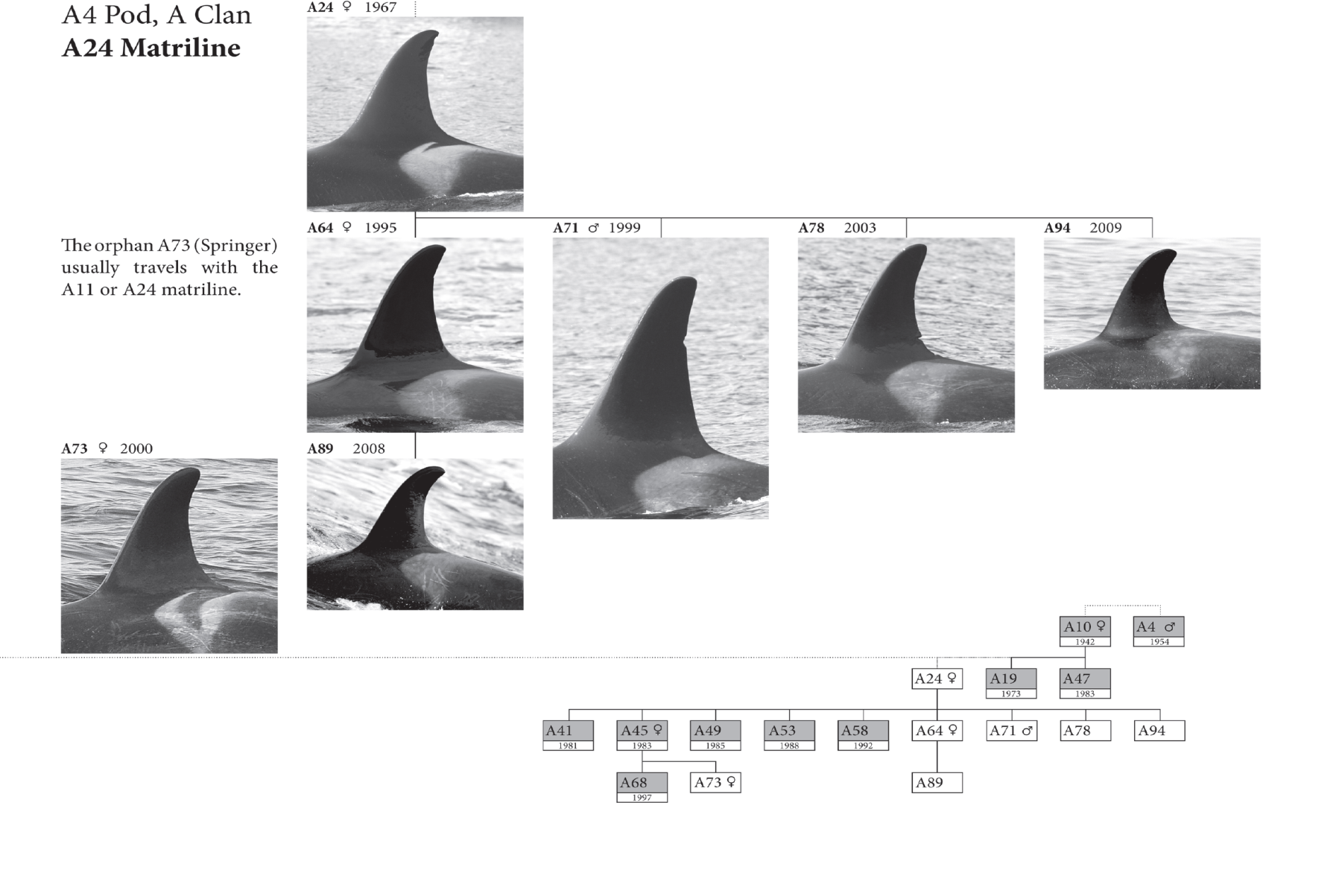

Resident killer whales also have the most stable social structure of the ecotypes found in our waters. They are matrilineal, which means that a female (matriarch), her sons and daughters, and her daughters’ offspring will all stay together for life. Each matriline has its own distinct acoustic call, much like a family badge, that calves learn from their mothers and family members.

A killer whale pod is a larger aggregation that can consist of several matrilines seen travelling together at least part of the time. It is thought that all matrilines in a given pod likely stem from one common female ancestor, and over time females with their growing families have gone off to form their own groups once their mothers have died. A clan is a group of pods that have similar-sounding vocalizations. In B.C., the northern resident population consists of A, G, and R clans, and the southern resident population consists of the single J clan.

It is known that killer whales have a life span and life history characteristics very similar to that of humans. They are known to live up to 100 years, become fertile starting at approximately age 10, and most interestingly, females go through menopause. This is a very rare phenomenon in the animal kingdom. Biologically speaking, survival past the reproductive age does not seem to serve a purpose. So why is it that we have non-reproductive grannies fearlessly leading each matriline? A recently published paper suggests that in many cases, post-reproductive females tend to take a strong lead in guiding the pod while searching for food, particularly in times of low salmon abundance. In other words, a grandmother killer whale might serve as a bearer of ecological knowledge that will help her family’s survival.

Mixing up the Gene Pool

If brothers and sisters never leave their own matriline, how do killer whales avoid inbreeding? This is a question that puzzled scientists for some time. In the 1990s and 2000s, Vancouver Aquarium scientist, Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard and others performed DNA research, and found that killer whales have a very sophisticated cultural breeding mechanism that promotes genetic diversity.

Dr. Barrett-Lennard was able to conduct paternity tests. The results revealed that with northern residents, mating typically occurs between the members of completely different clans; you will never see killer whales mating within their own matrilines. More recently, a similar study on southern residents carried out by Dr. Michael Ford found that, unlike northern residents, they have a greater tendency to inbreed. This is likely because the entire population is far smaller (81), and all southern residents belong to one single clan (J clan). They therefore lack the same acoustic diversity that we find in their northern counterparts. It has been observed that acoustically and genetically different pods of whales will come together for breeding purposes, and scientists believe that resident killer whales are able to tell how distantly related other whales are based on their vocal calls. Individuals will typically prefer mates with a very dissimilar call to ensure genetic diversity in their offspring. After breeding happens, pods and matrilines will continue on their own ways, each individual always travelling with their mother.

The matrilineal social structure of resident killer whales is so tight-knit that if an individual is missing during several encounters with a matriline, it is most likely that that animal has passed away.

We are able to identify each individual northern resident, southern resident, and Bigg’s (transient) killer whale in our waters based on unique physical characteristics of their dorsal fin. Each fin has a different shape, set of scratches and markings, and saddlepatch colouration, much like each person has a uniquely shaped fingerprint. Take a look at our recently edited ID catalogues of northern resident or Bigg’s killer whales in B.C.

The next time you see killer whales out on the water, snap a photo of their dorsal fins and report your sighting; we might just be able to figure out who you saw!

Posted July 27, 2015 by Vancouver Aquarium