Arctic Summer: Field Notes from Churchill River Estuary

With only a short window of time to gather data, multiple teams from Ocean Wise spent their summer in the Arctic for ongoing research. Studies included the distribution of microplastics in Arctic waters; tagging and tracking narwhals, Greenland sharks and other Arctic species; physical oceanography; research to monitor communication between mother beluga whales and their calves; and an underwater survey of Arctic marine species. Read on to find out more.

Aquablog post by Dr. Valeria Vergara, Ocean Wise Research Scientist

A bewildering array of sounds blasts through the speakers of our small research zodiac, but one call predominates, and it is unmistakable: the long, repetitive, maternal contact call that belugas produce when their calves are born, uttered in rapid, urgent succession. This allows calves to imprint on their mother’s contact call, as establishing an acoustic recognition system is paramount in a turbid underwater world where mothers and calves could easily lose sight of one another. After birthing their calves, belugas continue to produce this call type to rejoin their calves during temporary separations and in response to their calves’ calls. I had learned this some years ago at the Vancouver Aquarium, where I had the opportunity to study the vocalizations produced during three beluga births, to understand how beluga calves develop the rich repertoire of calls of this species.

Fast-forward to 2017. As a research scientist for Ocean Wise, a global conservation Organization headquartered at the Vancouver Aquarium, I have been generously supported by WWF this year to study, in collaboration with DFO, how we can use contact calls as indicators of behaviour, group composition and underwater noise disturbance. I am in the Churchill River Estuary, one of the three summering areas for the Western Hudson Bay beluga population, along with the Nelson and Seal river estuaries. This is one of seven distinct Canadian populations, identified as Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) largely due to the lack of protection measures in place for their summer or winter habitats. On this particular day, July 11th, we made it up river to a small shallow bay known as “Mosquito Point” (and the mosquitos here are indeed a force to be reckoned with!), an area where, according to local knowledge, the whales birth their calves. A broadband, highly sensitive hydrophone is connected to a speaker. When I hear those characteristic and familiar maternal contact calls, I immediately think “NEWBORN!” We look around. The water is muddy, the colour of coffee, due to the floods earlier this year, so we could only see fleeting fragments of beluga behaviour, but the newborn calf is easy to spot: it is right by our research boat, alone. It is so small one could see its fetal folds, and it still has that smooth shiny skin and light brown coloration typical of neonates.

The maternal contact-calls persist, loud and insistent, for 4 minutes. Are we hearing the mother of this calf, calling it? The acoustic quality of the calls, and the fact that they are produced exactly at the time when we witness a calf separation, certainly seem to indicate this. A few minutes later the calf disappears from view, and the calls cease. We hope that the mother-calf pair is reunited. This is the beauty of understanding the communication system of a sound-centered species. The sounds begin to act as indicators of what we might otherwise miss, such as whether there is a neonate in a group.

The study of beluga communication is intimately related to the omnipresent issue of underwater noise in the oceans. Water transmits sound much more rapidly and efficiently than air. The levels of underwater human-generated noise have increased at a staggering rate over the last sixty years. For beluga whales and other cetaceans that rely on sound for every aspect of their lives (to navigate, to find food, to communicate, to keep their social groups together, to maintain contact with their young) underwater noise must feel much like a thick layer of fog – biologists like to call it “acoustic fog” – as sound to these animals is like vision to us. To exacerbate this problem, the Arctic sea ice has been shrinking in surface area, bringing about increased access, more shipping traffic, and with this, noise. Although the Western Hudson Bay beluga population is relatively healthy, this species’ high site fidelity to their summering estuaries makes them particularly vulnerable to any disturbances in those estuaries.

The increased access and traffic may affect the Churchill estuary and its belugas in the not so distant future, but not this year. The Port of Churchill, Canada’s only deep-sea Arctic port, has been partially closed since last summer – with only two ships coming into the port during the entire 3-week duration of my field season. And the railway is not working either, as a result of over 2 km of rail-line submerged due to the heavy floods this spring, adding further financial stress to the people of Churchill and significantly decreasing ecotourism (the bread and butter of the town), including whale-watching. With such an unusually quiet estuary, this is a baseline year for our study. It will allow us to understand how often belugas use contact calls in this particular estuary, what their acoustic parameters are, and how prevalent these calls are under various group compositions (for example, all-male groups vs. mother and calf groups). We can then compare these data to future, busier years.

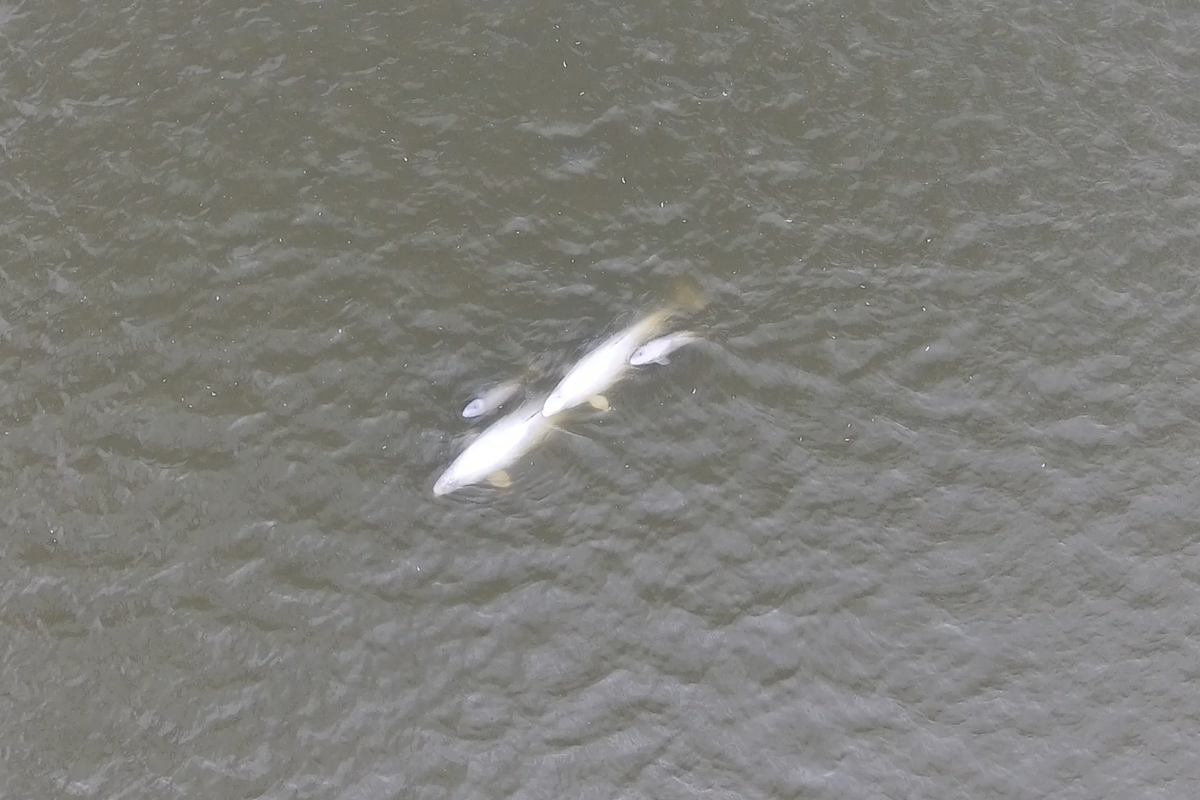

“I have them right under me! I see no little ones!” – says Justine, thrilled, while taking a peek at the screen of her iPad. It is July 13th. She is describing a beluga group that our small drone is hovering over. Justine is a University of Manitoba student conducting a parallel study on cortisol levels in beluga snot from the same research zodiac, and she has received the appropriate training and permits from Transport Canada to operate the small drone for this project, as a bird’s eye view of the whales often provides more accuracy than eye-level observations. We soon learned, however, that Churchill has a reputation for being a “Bermuda triangle” for drones. Magnetic interference prevents GPS reliability in some Arctic and Sub-Arctic areas, including Churchill. This means drones have to be flown on manual, a much less stable mode that can only be accomplished on calm days, which were few and far between. The wind in the estuary can be fierce, often creating large waves that rock our small boat dangerously (we did have to leave the water on a couple of occasions!). Year after year I re-learn the same lesson about fieldwork: it rarely goes as planned! This aspect of the study, pairing acoustic sessions with droning sessions, has been a bit slower than we ambitiously envisioned. But occasionally the relentless wind dies down and we can fly, and these sessions are priceless. July 13th is one such session. A light breeze allows us to fly over a group of 10 animals that we have been recording from our drifting zodiac, thus confirming that these are all adults, possibly males. It is exactly the type of control session we hope to obtain (i.e. no young in the recorded group) to learn more about separating group-types acoustically. I cannot wait to analyze this recording in detail: I suspect that maternal contact calls, and the underdeveloped pulse-trains characteristic of calves (they sound as if someone was running a finger through a comb) will be absent, in contrast to recordings of female-calf groupings.

With every passing season studying beluga whales in various areas of Canada I gain further insight into the extraordinarily rich communication system and profound sociality of this species. Churchill has been a strong reminder about their curious, inquisitive nature. Where else could a researcher obtain beluga snot by simply suspending a long pole with a petri dish fastened to its end over a curious beluga and wait until the animal exhales into the petri dish, without the most minimal sign that the animal cared one bit about the procedure? Pairing Justine’s cortisol data with our acoustic data will offer another layer of understanding about this baseline year.

Many long hours (months!) of acoustic analysis await me after a season that came and went much too quickly. I will miss this sub-arctic corner of Canada where not only beluga whales but also another iconic Arctic marine mammal species, polar bears, are a nearly daily sight. When you are recording a beluga group feeding on capelin out on the bay and you look up…and there are five polar bears on shore amongst a seagull colony, well…you watch them! There is a surreal feel to listening to one species while watching the other. For a little while this is our world. Our zodiac rocking on the Hudson Bay waves, the bears, the belugas all around us, the seagulls, the Arctic terns dive-bombing the bears, the wind. Everything else (my constant worries about the state of this planet, about the impact of global warming on ecosystems the world over, about belugas having to scream at each other through deafening human-made noise) is momentarily forgotten, and I simply am.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of WWF-Canada.

Posted September 20, 2017 by Vancouver Aquarium