CSI on the Ocean : Comment les chercheurs du site Ocean Wise apprennent à connaître les baleines grâce à l'ADN environnemental

When it comes to learning more about whales, researchers often need to tackle an important question – how do we study wild animals without bothering them?

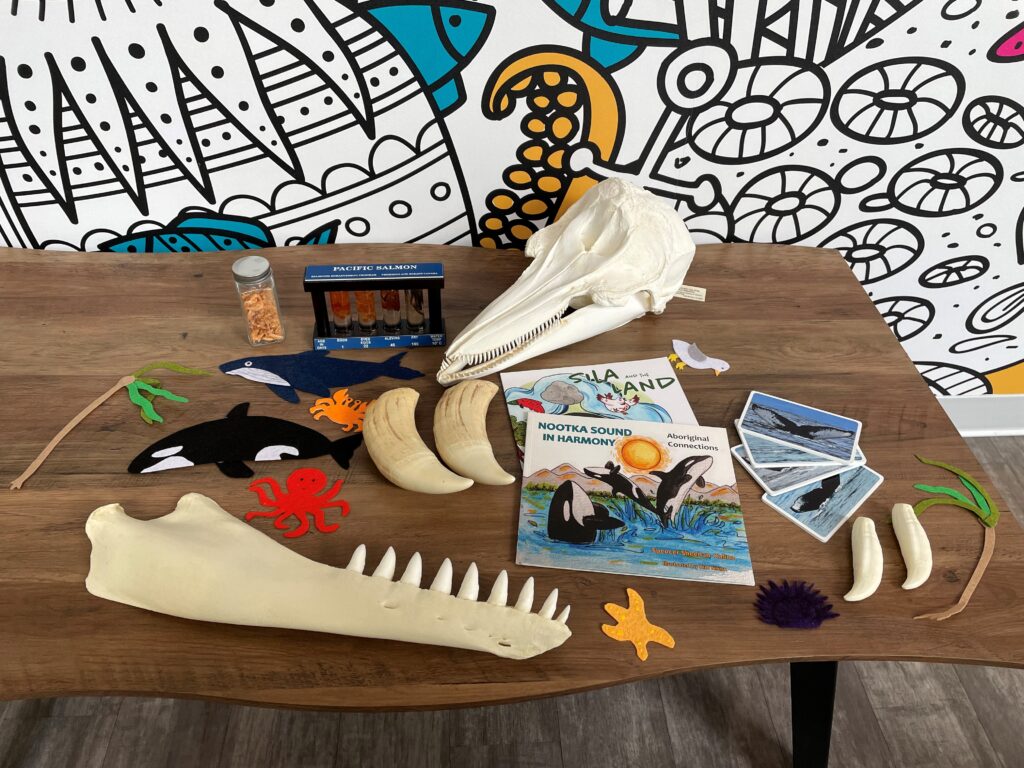

The Ocean Wise Whale Health and Monitoring Program uses cutting-edge science to monitor at-risk whale populations as well as develops novel conservation tools to protect whales from starvation. This pillar conducts applied research throughout the BC coast and includes a thriving, state-of-the-art Environmental DNA Laboratory in West Vancouver.

We chatted to Ocean Wise Whale Initiative Dr. Chloe Robinson and Environmental DNA Laboratory Coordinator Emma Laqua about how Ocean Wise is using eDNA to help protect vulnerable whale species – in a non-invasive way.

What is environmental DNA?

Dr. Chloe Robinson: Environmental DNA, or eDNA, is the DNA shed into the environment from different species. This DNA could be shed through skin cells, mucous, and other bodily secretions.

Emma Laqua: Researchers can collect eDNA from samples of soil, sediment, water, snow, air… etc! Here at the Ocean Wise Environmental DNA Lab, we are investigating cetacean (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) eDNA collected from their habitats.

eDNA has been described as “CSI on the ocean.” What have you learned about cetaceans through your eDNA work?

CR: In the same way that forensic teams scour crime scenes for DNA traces, we do the same thing in the ocean. We have found that we need to collect more water to detect smaller species such as harbour porpoise, and less water to detect larger species such as humpback whales.

EL: When cetaceans are foraging their prey can also leave behind fragments of eDNA in the water samples that we collect. From this, we’re learning more about the food sources of cetaceans like humpback whales and resident killer whales by sequencing and analyzing these pieces of prey eDNA. This can help us better understand their diets, what fish stocks are important, and what we can do to conserve these species.

How is Ocean Wise applying eDNA to researching cetaceans?

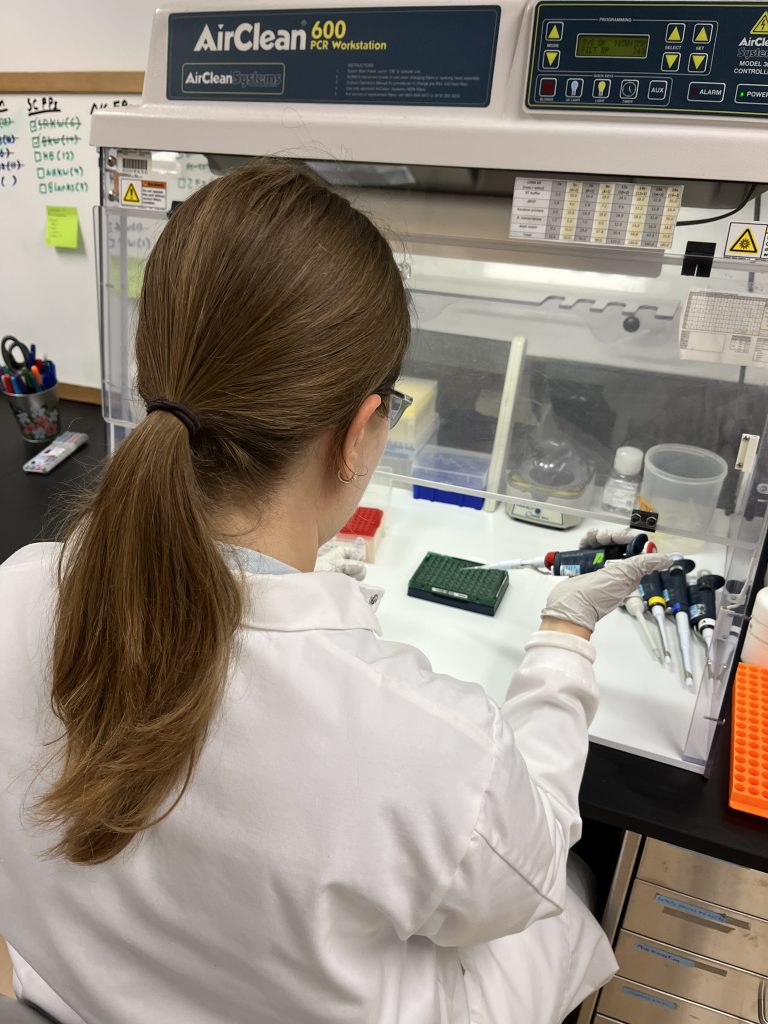

CR: Ocean Wise has been developing a lot of the single-species detection methods for cetaceans – this involves figuring out how much water is needed per species, what DNA markers are best to use, and how long the DNA hangs around in the environment. From this, we are then going to be looking at how much eDNA can tell us about individual whales – including their sex and individual genetic makeup – which can then inform how these animals are protected and conserved. We are also now moving our focus onto what the cetaceans are eating.

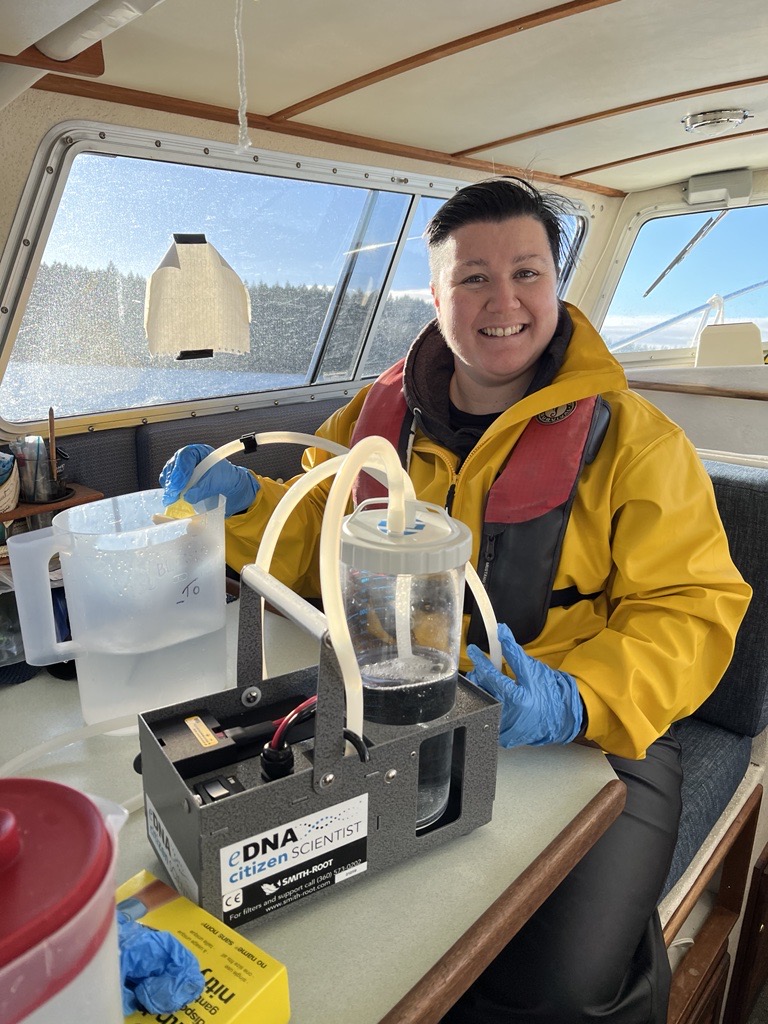

EL: We collect eDNA from cetaceans using something called a “flukeprint”. This is the bubbly patch of water left behind after a cetacean’s dive and it is enriched in their DNA! The fieldwork teams will take a scoop of a couple of litres of seawater from that flukeprint and then filter it to collect the eDNA. We have done a lot of tests to determine the amount of water to collect for a variety of different species and how quickly that water needs to be collected to detect whale DNA before it becomes degraded or diluted out in the ocean.

Another way that we’re using genetic sequencing is to study the population health and skin health of Bigg’s killer whales. We can examine this by sequencing the bacterial communities that make up a whale’s skin microbiome from the eDNA seawater samples. We are collaborating with the California Killer Whale Project to collect Bigg’s killer whale samples internationally!

What exciting discoveries has Ocean Wise made since starting this work?

CR: One of the most exciting things has definitely been our ability to determine the sex of most of the whales we have sampled. Especially for resident killer whales, they are such a well-studied population that we already know their sex, so we can compare those eDNA samples against known sexes to look at how effective it is.

EL: One great way that we can apply eDNA to cetacean research is by using it as another tool for surveys. Finding elusive and rare species like cetaceans out in the open ocean and near the coasts can be challenging. Standard survey methods include visual methods (with binoculars) and acoustic methods (with hydrophones) and we can also use eDNA in our surveys. So far, team members have designed and evaluated new PCR tests for detecting gray whale, Dall’s porpoise, and humpback whale eDNA and we’re continuing to work on tests for more species.

Pictured left: Emma sets up a set of qPCR reactions at the lab bench at the Pacific Science Enterprise Center. qPCR is the genetic test that we run to detect eDNA from flukeprints.

What is your background in environmental DNA?

CR: I started working with eDNA back in 2015 during my PhD at Swansea University (UK), which focused on using eDNA as a tool for detecting aquatic invasive species associated with aquaculture. From here, I then went onto refine methodology for collecting DNA from dolphin blows to look at respiratory health, as part of the SEACAMS research group. After this, I moved to Ontario, where I worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Guelph. In this role, I led a nationwide citizen science eDNA program ‘STREAM’, which looked at determining the health of freshwater systems across Canada using eDNA collected from sediment. I joined Ocean Wise in 2021 where I started leading the eDNA work across the coast with cetaceans.

EL: My first time collecting eDNA samples was when I did a summer internship in Ontario in 2021. I was part of a team that was detecting and assessing sea lamprey populations across the Great Lakes (they are an invasive and parasitic species) and that included collecting eDNA samples from rivers. Ever since then, I’ve been very excited about this field and the numerous questions we can answer using eDNA!

I also have lots of experience working in genetics labs. Previously I have worked in labs studying plant genetics and genomics, fish population genetics, and salmon genetics and genomics. I’m passionate about the ways that we can use genetics as a tool for conservation. I began working for the Ocean Wise Environmental DNA lab in 2023.

What excites you about using eDNA to research cetaceans?

CR: My dream is for eDNA to eventually replace the more invasive biopsy methodology as a way of getting DNA from individual cetaceans, and the fact we are getting closer to this reality makes me so excited! I feel that technology will have to improve somewhat before this happens but there is so much potential!

EL: eDNA is such an exciting tool to research cetaceans because it’s minimally invasive and doesn’t require using a biopsy dart to collect a blubber and skin sample. All we need to sample is 2-3.5L (depending on the species) of seawater. I’m looking forward to the ways that we can advance this tool and make future discoveries that inform conservation decision-making!

Is there anything else you would like to add about eDNA?

CR: Despite the price going down every year, collecting and analysing DNA samples still costs us a fair amount in materials and salaries. If anyone is interested supporting our eDNA work, please consider donating to the Ocean Wise Whales Initiative or symbolically adopting a killer whale through the Killer Whale Adoption Program. These funds also help us to refine and publish our methods, meaning more whales worldwide will benefit from this less-invasive approach of DNA collection.

EL: I second what Chloe said! The work the whales team does in the field and the lab relies on donations to the Ocean Wise Whales Initiative and funding from the Killer Whale Adoption Program.

Learn more about the Ocean Wise Whales Initiative here.

Posted August 13, 2024 by Rosemary Newton