Moins de 7 % des points chauds du globe où se produisent des collisions entre baleines et navires font l’objet de mesures de protection.

Les données d’Ocean Wise contribuent à un nouvel article, publié dans Science, sur les collisions entre les baleines et les navires à l’échelle mondiale.

D’après les archives fossiles, les cétacés – baleines, dauphins et autres espèces apparentées – sont issus de mammifères terrestres à quatre pattes qui sont retournés dans les océans il y a environ 50 millions d’années. Aujourd’hui, leurs descendants sont menacés par un autre mammifère terrestre qui est également retourné à la mer : l’homme.

Des milliers de baleines sont blessées ou tuées chaque année après avoir été heurtées par des navires, en particulier les grands porte-conteneurs qui transportent 80 % des marchandises échangées dans le monde à travers les océans. Les collisions sont la première cause de mortalité dans le monde pour les grandes espèces de baleines. Pourtant, il est difficile d’obtenir des données mondiales sur les collisions entre navires et baleines, ce qui entrave les efforts visant à protéger les espèces de baleines vulnérables. Une nouvelle étude publiée dans Science a quantifié pour la première fois le risque de collision entre les baleines et les navires dans le monde entier pour quatre géants des océans géographiquement répandus et menacés par le transport maritime : le rorqual bleu, le rorqual commun, la baleine à bosse et le cachalot.

Dans cet article, publié en ligne le 21 novembre 2024 dans Science, les chercheurs indiquent que le trafic maritime mondial chevauche environ 92 % des aires de répartition de ces espèces de baleines. L’équipe internationale à l’origine de l’étude, qui comprend des chercheurs de cinq continents, a examiné les eaux dans lesquelles ces quatre espèces de baleines vivent, se nourrissent et migrent en regroupant des données provenant de sources disparates – notamment des enquêtes gouvernementales, des observations faites par des membres du public, des études de marquage et même des registres de chasse à la baleine. L’équipe a recueilli quelque 435 000 observations uniques de baleines. Ils ont ensuite combiné cette base de données inédite avec des informations sur les parcours de 176 000 cargos de 2017 à 2022 – suivies par le système d’identification automatique de chaque navire et traitées à l’aide d’un algorithme de Global Fishing Watch – pour identifier les endroits où les baleines et les navires sont les plus susceptibles de se rencontrer.

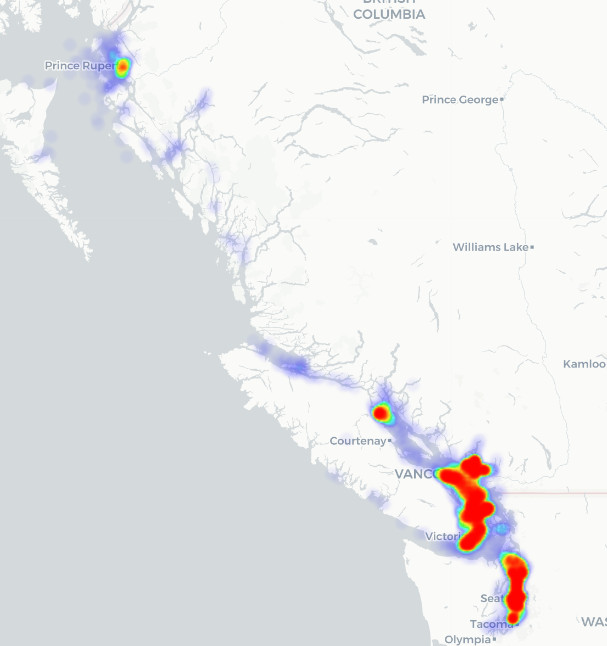

Chloe Robinson, directrice de l’initiative Ocean Wise Whales, et Lauren Dares, ancienne chercheuse scientifique d’Ocean Wise, sont les auteurs de l’étude et ont fourni des données et un aperçu des observations de baleines répertoriées dans l’ensemble de données de plus de 20 ans de l’Ocean Wise Sighting Network (OWSN). Ces données comprennent des observations de grandes espèces de baleines, à savoir la baleine à bosse, le rorqual commun, la baleine bleue et le cachalot, signalées dans l’État de Washington, en Colombie-Britannique et en Alaska.

C’est fantastique de voir comment les données de l’Ocean Wise ont été utilisées pour identifier les points chauds du risque de collision avec les navires pour les grandes espèces de baleines dans les eaux du nord-est du Pacifique. Nous espérons que l’exploitation des données pour cette étude contribuera à terme à la mise en œuvre de nouvelles mesures de gestion dans les zones à haut risque pour les baleines”, a déclaré le Dr Chole Robinson, directeur de l’initiative Ocean Wise Whales.

Les collisions entre les baleines et les navires n’ont généralement été étudiées qu’à un niveau local ou régional, par exemple au large des côtes est et ouest de la partie continentale des États-Unis, et les modèles de risque restent inconnus pour de vastes zones”, a déclaré l’auteur principal, Anna Nisi, chercheuse postdoctorale au Center for Ecosystem Sentinels de l’UW. Notre étude vise à combler ces lacunes et à comprendre le risque de collision avec des navires à l’échelle mondiale. Il est important de comprendre où ces collisions sont susceptibles de se produire, car il existe des interventions très simples qui peuvent réduire considérablement le risque de collision.

L’équipe a constaté que seulement 7 % des zones les plus exposées aux collisions entre baleines et navires ont mis en place des mesures pour protéger les baleines de cette menace. Ces mesures comprennent des réductions de vitesse, obligatoires ou volontaires, pour les navires traversant des eaux qui chevauchent les zones de migration ou d’alimentation des baleines.

Les zones les plus à risque pour les quatre espèces incluses dans l’étude se situent principalement le long des zones côtières de la Méditerranée, de certaines parties des Amériques, du sud de l’Afrique et de certaines parties de l’Asie.

L’étude a mis au jour des régions déjà connues pour être des zones à haut risque de collision avec des navires : La côte pacifique de l’Amérique du Nord, le Panama, la mer d’Arabie, le Sri Lanka, les îles Canaries et la mer Méditerranée. Mais elle a également identifié des régions peu étudiées présentant un risque élevé de collisions entre baleines et navires, notamment l’Afrique du Sud, l’Amérique du Sud le long des côtes du Brésil, du Chili, du Pérou et de l’Équateur, les Açores et l’Asie de l’Est au large des côtes de la Chine, du Japon et de la Corée du Sud.

L’équipe a constaté que les mesures obligatoires visant à réduire les collisions entre les baleines et les navires étaient très rares, ne chevauchant que 0,54 % des hotspots des baleines bleues et 0,27 % des hotspots des baleines à bosse, et ne chevauchant aucun hotspot des rorquals communs ou des cachalots. Bien que de nombreux hotspots de collision se situent dans des zones marines protégées, ces réserves n’imposent souvent pas de limites de vitesse aux navires, car elles ont été créées en grande partie pour lutter contre la pêche et la pollution industrielle.

Pour les quatre espèces, la grande majorité des points chauds pour les collisions baleine-navire – plus de 95 % – se situent le long des côtes, à l’intérieur de la zone économique exclusive d’un pays. Cela signifie que chaque pays pourrait mettre en œuvre ses propres mesures de protection en coordination avec l’Organisation maritime internationale des Nations unies.

Parmi les mesures limitées actuellement en place, la plupart se trouvent le long de la côte pacifique de l’Amérique du Nord et en mer Méditerranée. Outre la réduction de la vitesse, d’autres options permettent de réduire les collisions entre les baleines et les navires, notamment la modification des itinéraires des navires pour les éloigner des zones où se trouvent les baleines, ou la création de systèmes d’alerte pour informer les autorités et les marins de la présence de baleines dans les parages.

Le système d’alerte Ocean Wise Whale Report (WRAS) est l’un de ces outils d’atténuation. Le WRAS est un outil de conservation de pointe conçu pour protéger les baleines des collisions et des perturbations causées par les navires en alertant les marins de leur présence en temps réel. Le WRAS est alimenté par une combinaison de réseaux d’observation locaux et de détections automatisées à partir de caméras infrarouges et d’hydrophones. Ces données sont transmises aux navires en temps réel, ce qui permet aux marins de prendre des mesures proactives pour éviter les collisions avec les baleines.

“ Le système d’alerte des rapports sur les baleines est un outil conçu pour atténuer les collisions avec les navires. Depuis son lancement en 2018, plus de 60 000 alertes WRAS ont été envoyées aux navires commerciaux, contribuant à atténuer plus de 200 000 rencontres pour le risque de collision avec un navire. Comme le montre cette étude, les collisions avec les navires constituent un problème mondial et une menace pour la santé et la survie non seulement des quatre espèces de grandes baleines sur lesquelles porte cette étude, mais aussi de toutes les espèces de grandes baleines dans le monde. Nous savons que des stratégies telles que la réduction de la vitesse peuvent fonctionner, et nous pensons que le WRAS est un outil précieux qui peut être utilisé à la fois en conjonction avec des mesures existantes et mis en œuvre dans de nouvelles géographies non gérées pour réduire considérablement les collisions avec les navires”, a déclaré le Dr Robinson.

Pour en savoir plus sur les efforts déployés par Ocean Wise pour réduire les collisions avec les navires, consultez le site ocean.org/whales/wras/.

***

Les co-auteurs de l’étude sont Stephanie Brodie, chercheuse à l’Organisation de recherche scientifique et industrielle du Commonwealth en Australie ; les chercheurs Callie Leiphardt et Rachel Rhodes, et le professeur Douglas McCauley, tous de l’Université de Californie, Santa Barbara ; Elliott Hazen, écologiste chercheur au Southwest Fisheries Science Center de la NOAA ; Jessica Redfern, vice-présidente associée du Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life à l’Aquarium de Nouvelle-Angleterre ; Trevor Branch, professeur de sciences aquatiques et halieutiques à l’UW, et Sue Moore, chercheuse au Center for Ecosystem Sentinels ; André Barreto, professeur à l’Universidade do Vale do Itajaà au Brésil ; John Calambokidis, biologiste principal du Cascadia Research Collective ; Tyler Clavelle, scientifique spécialisé dans les données, David Kroodsma, scientifique en chef, et Tim White, responsable principal, Global Fishing Watch ; Lauren Dares et Chloe Robinson, scientifiques spécialisées dans la recherche, Ocean Wise ; Asha de Vos, d’Oceanswell au Sri Lanka et de l’université d’Australie occidentale ; Shane Gero de l’université de Carleton ; la biologiste Jennifer Jackson du British Antarctic Survey ; Robert Kenney, chercheur émérite de l’université de Rhode Island ; Russell Leaper du Fonds international pour la protection des animaux ; Ekaterina Ovsyanikova de l’université du Queensland ; et Simone Panigada de l’Institut de recherche Tethys en Italie.

La recherche a été financée par The Nature Conservancy, la NOAA, le Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, le National Marine Fisheries Service, Oceankind, Bloomberg Philanthropy, Heritage Expeditions, Ocean Park Hong Kong, National Geographic, NEID Global et la Schmidt Foundation.

Posted November 28, 2024 by Rosemary Newton