Arctic August: Beechey Island in the Snow

By John Nightingale, President & CEO, Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre

Before breakfast this morning, a boat-load of us took a trip to shore in the Zodiacs. We left early, around six o’clock, because our guides and our expedition leader, Aaron Lawton of One Oceans Expeditions, expected the winds to come up later in the day. So, we bundled up to face the temperatures hovering around zero degrees Celsius outside — cold enough that it snowed for about a half-hour.

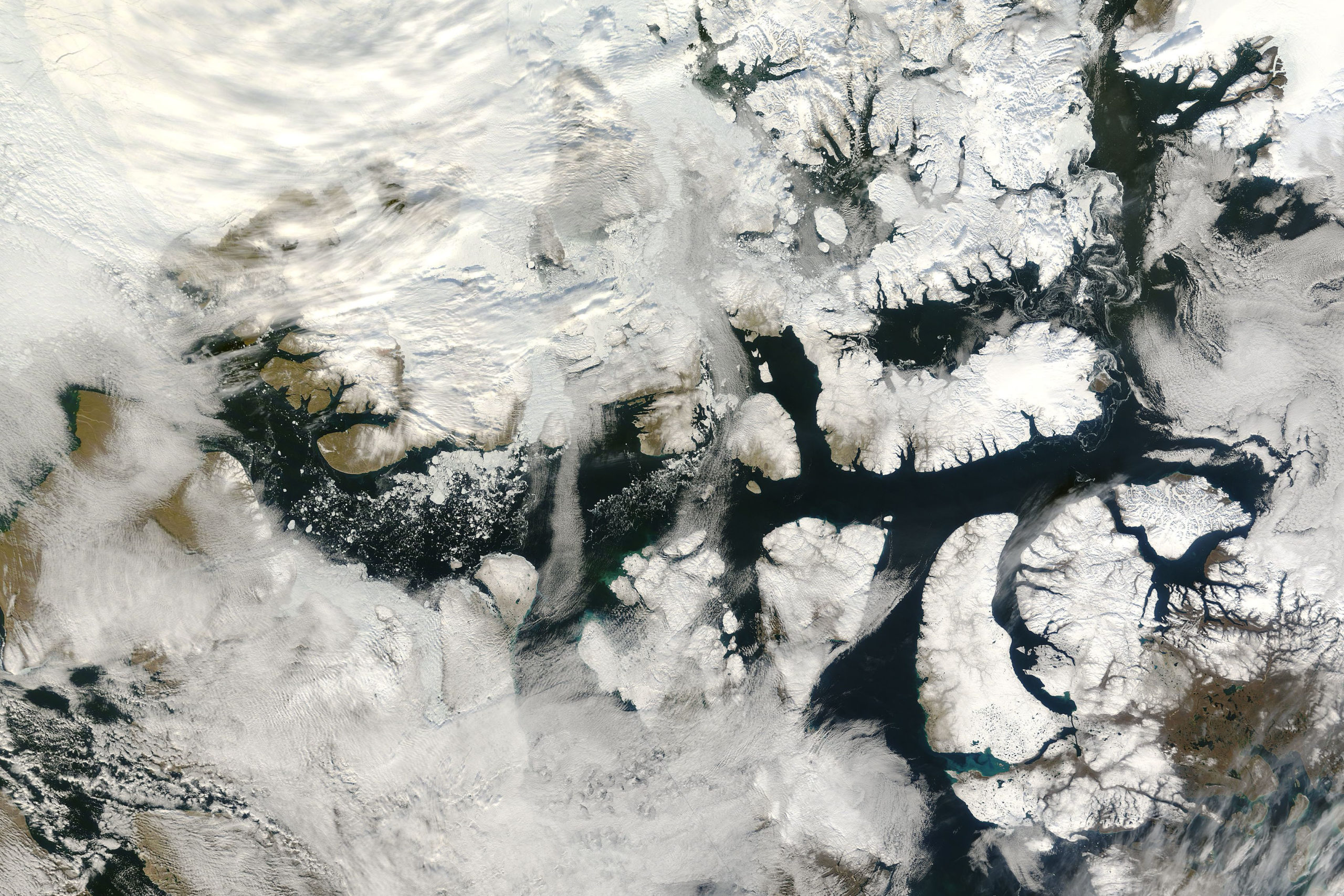

After a relatively short 300 meter trip to shore in thankfully windless conditions, we visited a major piece of Canada’s Arctic history —Beechey Island. In 1845 explorer Sir John Franklin, who commanded the ill-fated search for the Northwest Passage, chose the protected harbour of Beechey Island for their first winter encampment. The last time anyone, except the Inuit further south, ever saw HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (Franklin’s ships) was at Beechey Island. We anchored in the bay named after Franklin’s two ships which is a natural anchorage protected from almost everything except a wind coming from the south. We explored and got back on the ship by nine o’clock because the south wind had picked up, just as expected.

Beechey is gravelly much like most Arctic shorelines. The benches or flat areas of gravel at different elevations show both the changes in sea level over the past millennia, and the uplift of the ground after the glaciers melted. All over the Arctic the ground is still uplifting or rebounding — raising from a few millimeters per year to a centimeter or more in areas where glaciers have recently retreated or melted.

We also went to see the graves of men who had been on the Franklin expedition and had died and were buried there that first winter in the Arctic. We then walked along the shoreline to Northumberland House. This wooden house was built as a rescue or refuge house by search parties sent from England to look for the Franklin expedition. It had been stocked with barrels of food in the event the Franklin party returned to Beechey. But, as we all know, they never returned — their ships got trapped in ice during their trip south the next summer. They drifted for some time before the men abandoned ship and tried to make their way back overland to civilization.

Visiting the site caused many of our guests to question the protection and preservation of such significant historical sites. Canada is a very large country, the second biggest in the world, but with a relatively small population. Because our country is so large, our government has less money to spend per square kilometer compared to governments in most other developed countries in the world. There has never been adequate funding for thorough and systematic execution of environmental monitoring in the Arctic as well as the protection of such remote sites, and there likely never will be. Sites such as Beechey Island have relied on their remote location and rapidly developing code of conduct for tourism to help protect artifacts along with the site itself. This situation calls for innovative solutions, which fortunately, are being developed.

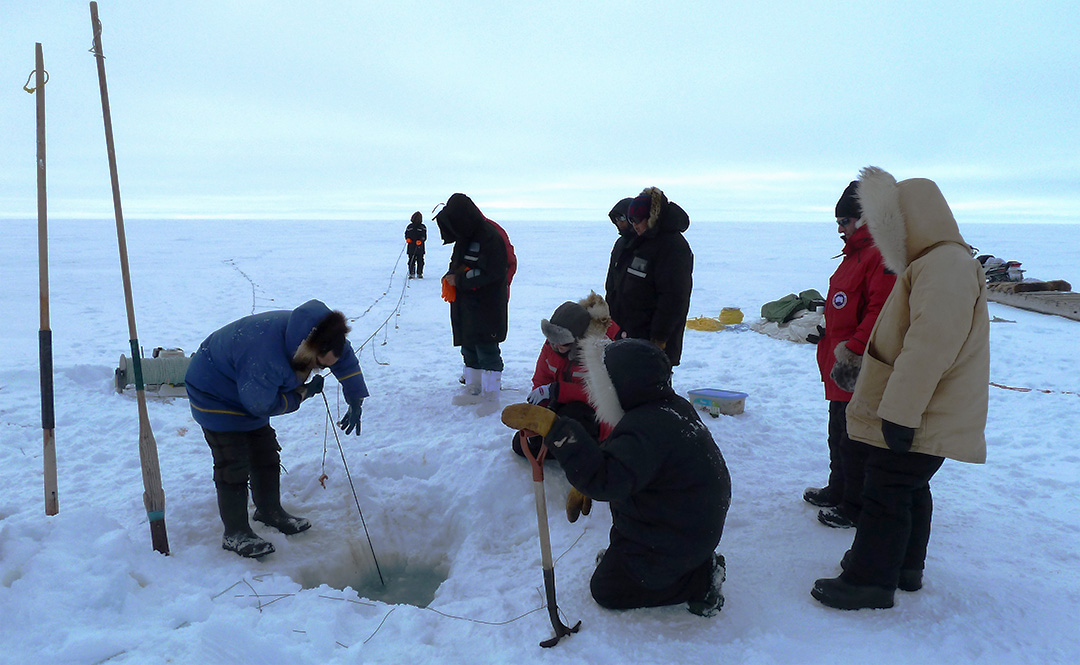

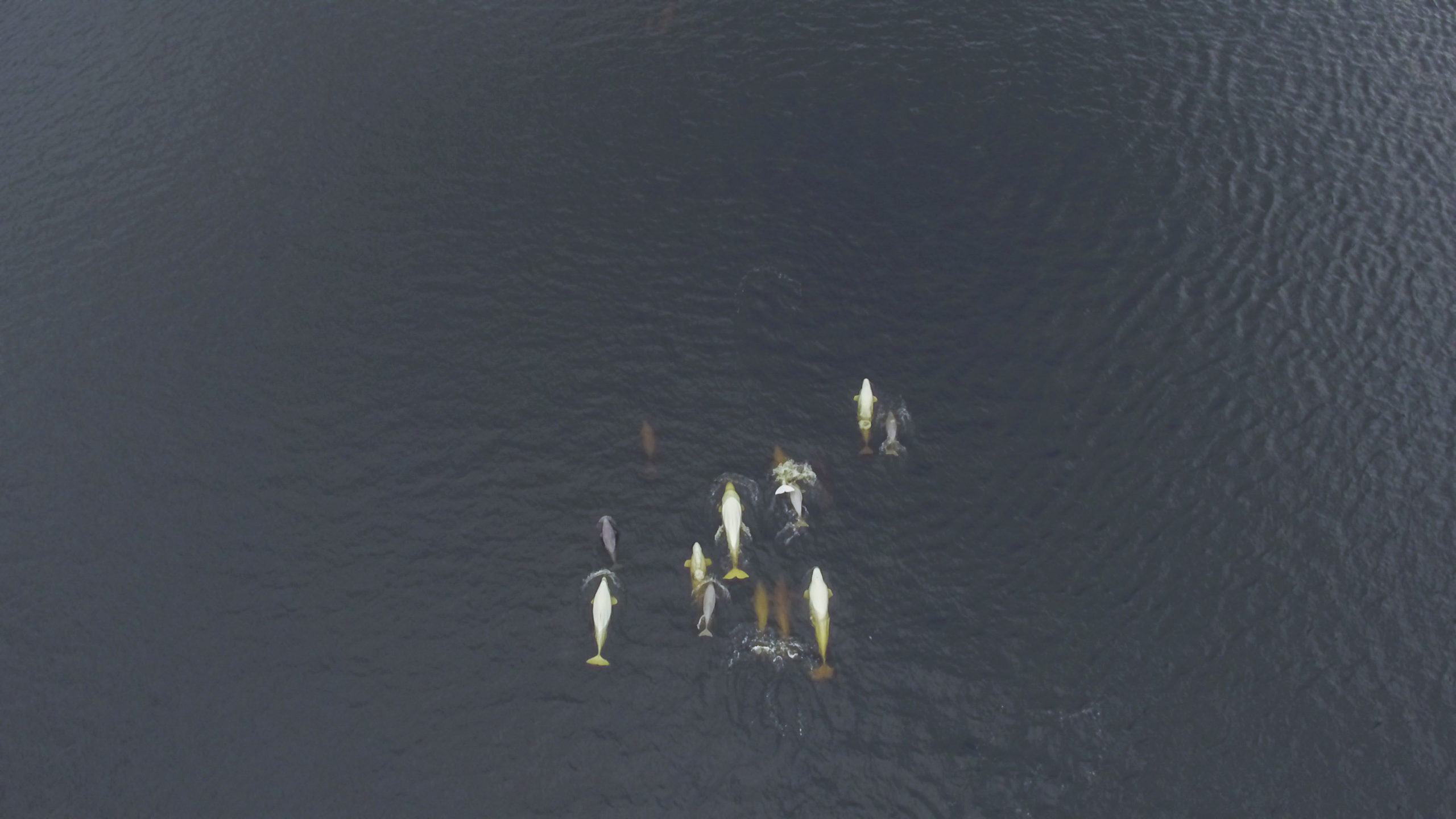

With global temperatures on the rise, we’re racing against time to gain insight about one of the least scientifically understood regions on the planet: the Arctic. This month, scientists from Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre head north to expand upon innovative Arctic research projects started in 2015, in collaboration with Polar Knowledge Canada (POLAR), the federal agency responsible for advancing Canada’s knowledge of the Arctic and for strengthening Canadian leadership in polar science and technology. This blog series chronicles our scientists’ time and research efforts in the Arctic.

Posted August 23, 2016 by Vancouver Aquarium